Theology Papers

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

The Thinker by Auguste Rodin, 1904

The Conflict Between Dispensationalism and Early Pentecostalism and the Emergence of the Latter Rain Motif by William Sloos

Abstract:

Confronting the early Pentecostal movement was dispensationalism, a prevailing fundamentalist theology that conflicted with Pentecostal ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives. Although early Pentecostals concurred with most dispensational teachings, their experience of Spirit-baptism prevented them from accepting two significant dispensationalist tenets: 1) spiritual gifts had ceased following the apostolic period and 2) the church age would end in apostasy. To early Pentecostals, the charismatic gifts were being restored to the church in preparation for a global end-times revival. This difference in ecclesiology and eschatology set the early Pentecostals at odds with the pessimistic nature of dispensational hermeneutics. Having difficulty explaining their charismatic experiences through dispensational language, Pentecostals would turn to the latter rain motif to articulate their emerging distinctives. This article examines the conflict between dispensationalism and early Pentecostalism and explores how early Pentecostals adopted the latter rain motif as an alternative theological framework to articulate their ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives.

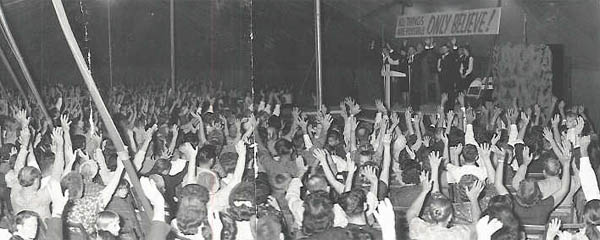

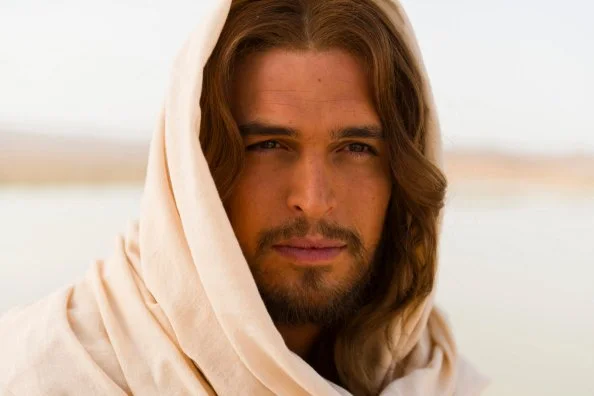

Early Pentecostal Revival Service in America

Introduction

Following the birth of the Pentecostal movement in the early twentieth century, Pentecostals were confronted with dispensationalism, a prevailing fundamentalist theology that conflicted with their emerging ecclesiastical and eschatological distinctives.{C}[1] Developed in the mid-nineteenth century by John Nelson Darby, dispensational theology was a system of interpreting biblical history as a series of successive dispensations culminating in a clearly defined eschatological framework.[2] Although early Pentecostals concurred with most dispensational hermeneutics, their experience of Spirit-baptism prevented them from accepting two significant dispensationalist tenets: 1) the gifts of the Holy Spirit had ceased following the apostolic period and 2) the church age would end in apostasy.[3] Clearly apparent to Pentecostals, the charismatic gifts had not ceased after the apostolic age, but were now being restored to the church through the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.[4] Moreover, because of the restoration of the charismatic gifts, the church age would not end in apostasy, but rather the church will experience a global end-times revival prior to the imminent return of Christ. This significant difference in ecclesiology and eschatology set the early Pentecostals at odds with dispensationalism. Unable to explain the theological implications of their charismatic experience through dispensational theology, Pentecostals would turn their attention to the latter rain motif to articulate their emerging distinctives.[5] This paper examines the conflict between dispensationalism and early Pentecostalism and explores how early Pentecostals found an alternative theological framework to articulate their ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives.

The Origin and Nature of Dispensationalism

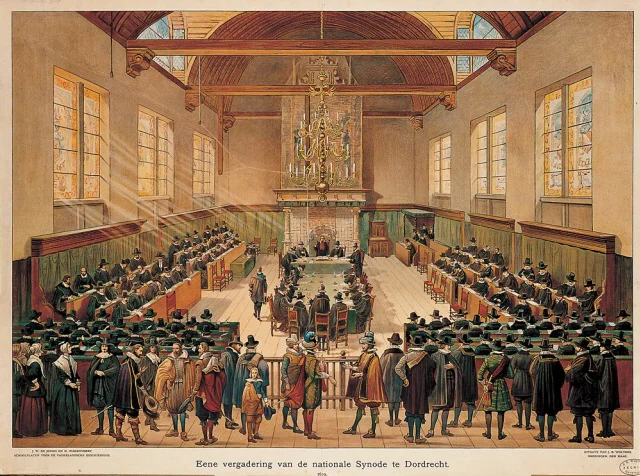

Although dispensational theology is not expressly covered in the ancient creeds of the church, throughout history theologians have endeavoured to map the divine timeline marked out in Scripture.[6] Emerging as a formal comprehensive system of biblical interpretation, dispensationalism was first developed by an early nineteenth century group of theological students in the early Brethren movement in Ireland.[7] John Nelson Darby (1800-1882), a former Church of Ireland cleric, formally systemized the hermeneutical scheme and subsequently exported the highly eschatological interpretive methodology to North America during a time of heightened end-times expectations.[8] Helping to popularize Darby’s innovative exegesis, Rev. Dr. C. I. Scofield published the Scofield Reference Bible (1909) which intertwined dispensational teachings with prophetic and apocalyptic literature in the King James Version of the Bible.[9] Despite allegations regarding Scofield’s questionable financial dealings, bigamy, and falsifying a doctoral degree, he sold millions of copies and helped to firmly cement dispensational theology in the fundamentalist doctrines of early twentieth century evangelicalism.[10] For evangelicals, dispensational theology not only upheld the fundamental truths of Scripture that were under attack by the rising tide of Modernism, but also provided a fitting interpretive system to understand end times prophecy that appeared to be unfolding around them.

As a systematized concept of biblical interpretation, dispensational theology describes how God manages the affairs of humankind in specific time periods or dispensations throughout history.[11] Each dispensation is comprised of a unique governmental relationship between God and humanity and includes a particular responsibility placed upon humanity in accordance with each governing relationship. As well, each dispensation has its own requisite demands for faith and obedience according to God’s progressive revelation.[12] Beginning with creation and moving throughout history, each successive dispensational epoch is characterized by a common pattern consisting of a test of faith to determine whether people will choose to align themselves with God’s economy, followed by their inevitable failure and subsequent judgment for disobedience.

Based upon the consistent use of a normal, plain, or literal interpretation of Scripture, dispensational theology insists there are seven dispensations that can be deduced from the Scriptures.[13] The seven dispensations are as follows:

1. Innocence (between creation and the Fall, see Gen. 1:28)

2. Conscience or Moral Responsibility (between the Fall and Noah’s flood, see Gen. 3:7)

3. Human Government (from the flood to the call of Abraham, see Gen. 8:15)

4. Promise (from Abraham to Moses, see Gen. 12:1)

5. Law (from Moses to the death of Christ, see Ex. 19:1)

6. Church (from the resurrection to the present, see Acts 2:1)

7. The Kingdom or The Millennium (see Rev. 20:4).[14]

The church age, also known as the dispensation of grace, begins with the resurrection of Christ and ends with the rapture of the church, followed by a seven year tribulation period where God pours out his wrath on an unbelieving world and apostate church.[15] In addition to this complex dispensational system, there is also a clear distinction between Israel and the church.[16] Dispensational teachers have contended that, throughout history, God has pursued two separate soteriological programs, one program involving the church or the “heavenly people” and the other involving Israel or the “earthly people.”{C}[17] The church, comprised of both Jew and Gentile believers, is considered an independent program that does not advance or fulfil any of the biblical promises given to Israel. The present church age is regarded as a period in which Israel is temporarily set aside from the dispensational program, but when the church is raptured, God will then proceed with fulfilling his eschatological purposes for national Israel. The return of the Jews to Palestine in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries made many evangelicals especially receptive to the eschatological system of dispensational theology and aided in creating and sustaining an expectation that the church age was drawing to a close, the rapture was imminent, and God was about to turn his attention back to Israel.[18]

An Emerging Pentecostal Ecclesiology and Eschatology

Within this heightened eschatological context of the early twentieth century, the Pentecostal movement exploded onto the religious landscape with an emphasis on the baptism of the Holy Spirit with speaking in tongues according to the biblical pattern of the first Pentecost in the book of Acts.[19] In North America, the epicentre of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was the Apostolic Faith Mission at Azusa Street in Los Angeles, where people from all over the world came to seek the Lord for their personal Pentecost.[20] With three services a day, seven days a week, for forty-two months, thousands of seekers received an ecstatic spiritual experience that revived their faith and transformed their lives. In addition to the baptism of the Holy Spirit, people attending services at Azusa Street also reported experiencing conversions, healings, miracles, deliverances from addictions, and exorcisms. Arising from these experiences was a revitalized ecclesial praxis that centered upon the restoration of the charismatic gifts according to the apostolic paradigm. Illustrating the significance of this apostolic restoration, Seymour proclaims, “All along the ages men have been preaching a partial Gospel…He is now bringing back the Pentecostal baptism to the church.” With optimistic certainty, Seymour adds “The Lord is restoring all the gifts to His Church” and “it is heaven below.”[21] Unlike the pessimistic views of dispensationalism, early Pentecostals believed that they were experiencing the reclamation of all that had been lost through the centuries, the recovery of the power and gifts of the Holy Spirit, and the reviving of the one true church of Christ. This new ecclesiology led Pentecostals to consider themselves, not merely another denomination, but rather a divinely initiated movement designed to restore the fullness of the Holy Spirit evidenced by miracles, healings, signs, and wonders.

In conjunction with the emerging Pentecostal ecclesiology, the restoration of the charismatic gifts also led to the development of a uniquely Pentecostal eschatology. Believing that the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was the fulfilment of Bible prophecy and signalled the arrival of the “last days,” Pentecostals were consumed with actively and urgently proclaiming the gospel prior to the imminent return of Christ.[22] This emotive end-times sentiment pervaded early Pentecostal communities and fuelled their homiletics, periodicals, and missionary endeavours. Emanating from Pentecostal pulpits, preachers urged listeners to ready themselves for Christ’s return. Early Pentecostal publications would also reverberate with the pressing message of the imminent return of Christ and the important task of witnessing to lost people before the end of the age. The impending eschaton also inspired many Pentecostals to serve on foreign mission fields with the conviction that every person must hear the gospel before Christ breaks through the clouds. Anderson states, “The significance of this teaching for Pentecostals was that their belief in the ‘soon’ coming of Christ with its impending doom for unbelievers lent urgency to the task of world evangelization.”{C}[23] Confident that the restoration of the apostolic church was a clear indicator of the shortness of time, Pentecostals made evangelism their primary concern and viewed themselves as participants in the global harvest. “This is a world-wide revival,” declares Seymour, “the last Pentecostal revival to bring our Jesus. The church is taking her last march to meet her beloved.” “We are expecting a wave of salvation go over this world…There is power in the full Gospel. Nothing can quench it.”{C}[24] Rather than the present dispensation ending in apostasy, Pentecostal expectations were charged with enthusiastic optimism that they were partners with Christ in the last days. Deeply rooted in charismatic experience, these ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives soon established themselves within the emerging Pentecostal community and became the pervading ethos that characterized the movement in its earliest years.{C}[25]

The Conflict between Dispensationalism and Pentecostal Distinctives

Conflicting with the developing ecclesiology and eschatology of the burgeoning Pentecostal movement was the prevailing dispensational doctrines dominating the current evangelical culture. Despite having an affinity with many elements of dispensational hermeneutics, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit created an obvious theological quandary for early Pentecostals.[26] Dispensational theology teaches that the Pentecostal experience of the baptism in the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, and the sensational or sign gifts of the Spirit were not normative for the church age, but were only intended to inaugurate the church and terminated after the apostolic period. “Tongues and the sign gifts are to cease,” states Scofield’s commentary on spiritual gifts.[27]{C} Moreover, dispensational views also stipulate that each dispensation, including the church age, concludes in human failure and apostasy, setting any conception of an end-times revival at variance with the established dispensational paradigm. As Scofield emphasizes repeatedly throughout his text notes, “the predicted future of the visible Church is apostasy”[28] and “the only remedy for apostasy is judgment” and “catastrophic destruction.”[29] He adds, “The predicted end of the testing of man under grace is the apostasy of the professing church and the resultant apocalyptic judgments.” Inherently pessimistic, dispensationalism presents a powerless church with a degenerating future. With Pentecostals enjoying the restoration of charismatic power and gifts along with increasing reports of global revival, dispensational theology became increasingly inconsistent with the Pentecostal experience. Alert to these variants, some outspoken dispensationalists judged the budding Pentecostal phenomenon as unbiblical and even sourced in the demonic; a theological wedge was widening between the two camps.[31]

Since early Pentecostalism had not formed a satisfactory explanation for their emerging distinctives, many early Pentecostal leaders tried to articulate their theological understanding by using various forms of familiar dispensational language. Evidence of these theological inconsistencies can be found scattered throughout early Pentecostal writings, highlighting the challenge Pentecostals had in defining their ecclesiology and eschatology against traditional dispensational theology. To illustrate, William Seymour comments about the restoration of Pentecost but then states that “we are living in the eventide of this dispensation.” Charles Parham borrowed much of his eschatology from dispensational theology despite the inherent conflicting ideas. Often attempting to merge the Pentecostal experience with dispensational hermeneutics, Parham teaches that the “last days” would be marked both by the restoration of the apostolic church and also by great apostasy.[34] This theological paradox continues with William Durham who also tried integrating Pentecostal restoration with dispensational theology stating, “In the end of the days the Lord has poured out His Spirit, as in the beginning of the dispensation, and has undertaken to restore to His own spiritual church all that she has lost through the failure and unbelief of man.”[35] Numerous early Pentecostal teachers employed dispensational language to describe the outpouring of the Holy Spirit despite the obvious inconsistencies. Without a suitable framework to interpret the Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit, early Pentecostal leaders struggled to assimilate their charismatic distinctives with popular dispensationalism and began turning their attention to the latter rain motif.

The Latter Rain Motif

The concept of the latter rain motif did not originate with the birth of the Pentecostal movement, but was developed out of nineteenth century Wesleyan-Holiness teachings.[36] Nevertheless, the latter rain motif would become the prevailing theological methodology for framing the restorationist phenomena that pervaded early Pentecostal thought. Developed from a typological reading of some Scripture passages, the basis for the latter rain metaphor asserts that the chronology of the church spiritually parallels the rainfall patterns in early Palestine.[37] The term is initially found in Deuteronomy 11:10-15 where God promises the Israelites that, if they would serve him with all their heart and soul, he would give them the “early” and “latter” rain.[38] According to ancient Mediterranean agricultural customs, to produce a bountiful harvest, a farmer requires rain at two critical points in the growing cycle.[39] Following the planting, the first or “early rain” is needed to cause the seed to germinate. Additionally, just before the crop is harvested, a “latter rain” is needed so the grain will produce a high yield at harvest time. In Joel 2:23 and 28, this agricultural model is reconfigured as a prophetic metaphor to indicate the divine timeline for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the church age. The first outpouring of the Holy Spirit occurred on the day of Pentecost in Acts 2, symbolizing the “early rain” that gave life to the church. Between the early and latter rains was the long, arid period of Christendom’s apostasy and corruption during the Middle Ages. When the second outpouring of the Holy Spirit occurred at the dawn of the twentieth century, it was indicative of the “latter rain,” spiritually saturating the land in preparation for the great harvest of souls before the coming of the Lord. For early Pentecostals, the latter rain motif complemented their experience and affirmed the restorationist and revivalist ethos that defined the movement.[40] As opposed to dispensationalism, which rejected the possibility of an end-times outpouring of the Holy Spirit, adopting the latter rain motif provided biblical legitimacy to the emergent Pentecostal movement and affirmed the existing notion among early Pentecostals that they were part of God’s overall eschatological timetable.[41]

Embracing the latter rain motif gave the early Pentecostals a fitting theological framework to articulate their ecclesiology and eschatology. Although they never discarded the dispensational doctrines of salvation history and most elements of Bible prophecy, the latter rain motif became the primary apologetic for the Pentecostal movement and gave Pentecostal proponents a meaningful and emotive biblical apologetic to explain the restoration of the charismatic phenomenon. Reflecting on the emphasis early Pentecostals placed on the latter rain motif, Blumhofer states:

While they [early Pentecostals] unquestioningly embraced most of Darby’s view of history, early Pentecostals rejected his insistence that the “gifts” had been withdrawn. They introduced into his system their own dispensational setting where the gifts could again operate in the church. The device through which they legitimated those gifts was their teaching on the latter rain.[42]

For early Pentecostals, the adoption of the latter rain motif seemed to remedy the theological impasse with dispensationalism- at least within the Pentecostal community. By superimposing the latter rain motif onto dispensational theology, Pentecostals retained a relatively functional framework for interpreting prophecy and enjoyed biblical support for their charismatic experience. Despite the inherent inconsistencies with merging these two theologies, the pragmatism of the early Pentecostals creatively negotiated between the conflicts and charted a new theological trajectory towards the development of a uniquely Pentecostal theology.[43]

The latter rain motif quickly took root in early Pentecostal publications throughout North American and came to define the ecclesiology and eschatology of the fledgling Pentecostal movement. Many started calling the Pentecostal revival the “Latter Rain Movement” after one of Parham’s published reports describing the beginning of the outpouring of the Spirit at the turn of the century.[44] Additionally, articles began circulating with titles such as, “The Promised Latter Rain Now Being Poured Out on God’s Humble People,” and “Gracious Pentecostal Showers Continue to Fall.”[45] Around the same time, a Pentecostal periodical out of Chicago assumed the banner “Latter Rain Evangel,” emphasizing the increasing popularity of the latter rain sentiment throughout the Pentecostal movement.[46] Seymour asserts that God “gave the former rain moderately at Pentecost, and He is going to send upon us in these last days the former and latter rain” (italics mine).[47] W. C. Stevens describes Pentecost as “saturating rains” marked by “atmospheric convulsions” breaking out “here and there in identical kind in various localities.”[48] David Wesley Myland, a Canadian-born Pentecostal pastor, wrote an influential book describing the early Pentecostal movement entitled “The Latter Rain Covenant (1910).”[49] Fused with “latter rain” thematic expressions, his book relates the prevailing eschatological ethos among early Pentecostals. Believing that they were living in the final “cloudburst” of Holy Ghost power, Myland wanted everyone to get “totally soaked” by the “latter rain” which was falling so copiously from heaven.[50] Although the latter rain metaphor had its limitations, early Pentecostals used it liberally to articulate their ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives and their favourable position within God’s plan of redemption history.

Despite the early Pentecostals’ innovative synthesis of the latter rain motif with dispensational theology, the fundamentalists were not amused. Already strongly disapproving of Pentecostal devotional ethics and restorationist claims, when the Pentecostals creatively modified dispensational theology to accommodate their charismatic experiences, a deep and long-lasting wedge was placed between the two religious groups. While Pentecostals treated the dispensational interpretive framework with value and even willingly promoted the sale of the Scofield Reference Bible, the fundamentalists were staunchly opposed to the “Pentecostal distortion.”[51] Blumhofer states:

Dispensationalism, as articulated by Scofield, understood the gifts of the Spirit to have been withdrawn from the Church. Rejecting the latter rain views by which Pentecostals legitimated their place in God’s plan, dispensationalists effectively eliminated the biblical basis for Pentecostal theology; and although Pentecostals embraced most of Scofield’s ideas…they remained irrevocably distanced from fundamentalists by their teaching on the place of spiritual gifts in the contemporary church.[52]

Regardless of the opposing opinions between fundamentalists and Pentecostals, the early Pentecostals could not deny their experience. Whether their experience was accepted or rejected by fundamentalists was irrelevant; the emergence of the charismatic gifts were irrefutable proof that God was restoring his church. Driving the Pentecostal movement was not doctrines, creeds, or theological constructs, but an intense spirituality sustained by an equally intense conviction that what they were experiencing was not only biblical, but was also a prophetic fulfilment of God’s eschatological agenda.[53] Moreover, the ensuing division between fundamentalists and Pentecostals became a catalyst for furthering the development of a more defined Pentecostal ecclesiology and eschatology that went beyond the latter rain motif towards a more well-informed biblical and theological context in the following decades.[54] Although dispensational theology maintained its usage in Pentecostal circles throughout the twentieth century, the development of the latter rain motif enabled early Pentecostals to biblically support their unique distinctives in the midst of opposing theological viewpoints.

Conclusion

Within the heightened eschatological context of the early twentieth century, the Pentecostal movement burst onto the religious landscape. The emergence of the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the charismatic gifts signalled to Pentecostal believers that they were experiencing the end-times restoration of the apostolic church. Confronting the early Pentecostal movement was dispensationalism, a prevailing fundamentalist theology that conflicted with the emerging Pentecostal ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives. Dispensational hermeneutics insisted that the charismatic gifts had ceased following the apostolic age and the church age would end in apostasy prior to the return of Christ. To the early Pentecostals however, it was visibly evident that the Holy Spirit was empowering the church for a global end-times revival. Unable to explain the theological implications of their Pentecostal experience through dispensational theology, Pentecostals adopted the latter rain motif according to the prophecies in the book of Joel which anticipated a “last days” outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Believing the “early rain” to be the first Pentecost in the book of Acts, the early Pentecostals were certain they were now experiencing the “latter rain” of the Holy Spirit in preparation for a great harvest of souls prior to the imminent return of Christ. Although early Pentecostals retained most elements of dispensational theology, the latter rain motif became a dominant apologetic for the early Pentecostal movement and provided an adequate theological framework to articulate their emerging ecclesiological and eschatological distinctives. As the Pentecostal movement progressed, a more defined Pentecostal theology developed, but the latter rain motif remains an integral part of understanding early Pentecostal thought in the midst of conflicting theological opinions.

The History of the Future: Examining the Historical Development of Eschatology in the PAOC by William Sloos

(Presented at PAOC General Conference, Saskatoon, April 2014)

Eschatology has been a central feature of our movement. More than simply a theological component in our doctrine, the expectation of the Second Coming of Christ has stirred our faith, captivated our hearts, lifted our worship, punctuated our preaching, and fueled our missions. Since the earliest days of Pentecostal ministry, the end times has seized the imagination, ethos, and enthusiasm of Pentecostal believers. [S3] In 1908, A. H. Argue proclaims that this “present outpouring of the Spirit…is the last call before Jesus comes again.”[1] R. E. McAlister motivates his readers, “The Latter Rain is falling. Jesus is coming soon. Get ready to meet Him!”[2] Convinced they were living in the eleventh hour, just minutes before the midnight call, Pentecostals separated themselves from the world, tarried at altars for power, and testified to signs, wonders, and miracles. As the century progressed, cultural, economic, and geo-political shifts influenced our attitudes toward eschatology. As well, our perspectives on biblical interpretation matured through rigorous theological study and dialogue. Despite these changes, our original doctrinal statement on eschatology has remained relatively unchanged since its inception in 1927, having only undergone one revision in 1984. Now thirty years later, we are reviewing our doctrine on eschatology again to ensure that our current statement is relevant to our ministries, empowering our leaders, and informing our parishioners.

Anchoring our session today is one key question for Pentecostal leaders to consider: Is our eschatological system, as seen in our Statement of Faith and Essential Truths, still serving us well? Our current statement is available at your table for your review. To assist in our discussion, I will briefly examine the historical development of the doctrine of eschatology within our movement- a history of the future, if you will. We will review the following:

a) The Theological Roots of Pentecostal Eschatology

b) Early Pentecostal Eschatological Thinking

c) A Survey of PAOC Eschatological Doctrinal Changes

This brief historical reflection is intended to provide a necessary background and a proper context to engage in our dialogue today. Following this presentation, Dr. Van Johnson will return to guide our round-table discussions.

A. The Theological Roots of Pentecostal Eschatology

The roots of Pentecostal eschatology are found in dispensationalism- an innovative theological system crafted to map out the divine timeline marked out in Scripture. Emerging as a comprehensive scheme of biblical interpretation, dispensationalism was first developed in the early 1800’s by a group of theological students in the Brethren movement in Ireland.[4] John Nelson Darby (1800-1882), a former Church of Ireland cleric, pieced together the hermeneutical system and exported the interpretive methodology to North America during a time of heightened end-times expectations: the American Revolution (1776), the French Revolution (1789), Napoleon’s march across Europe (1803-1815), the decay of the Ottoman Empire, the iniquities of the Roman Catholic Church, and the rise of nationalism, communism, and anarchy.[5] Helping to popularize Darby’s innovative exegesis, Rev. Dr. C. I. Scofield published the Scofield Reference Bible (1909) that intertwined dispensational teachings with prophetic and apocalyptic literature in the King James Version.[6] Despite allegations regarding Scofield’s questionable financial dealings, bigamy, and falsifying a doctoral degree, he sold millions of copies and helped to firmly cement dispensational theology in the fundamentalist doctrines of early twentieth century evangelicalism.[7] For evangelicals, dispensationalism not only upheld the fundamental truths of Scripture that were under attack by the rising tide of Modernism, but also provided a fitting interpretive system to understand end times prophecy that appeared to be unfolding around them.

As a system of biblical interpretation, dispensationalism describes how God manages the affairs of humankind in specific time periods or dispensations throughout history.[8] Based upon a literal reading of Scripture, dispensational theology insists there are seven dispensations that can be deduced from the Scriptures:[9]

1. Innocence (Creation to Fall, see Gen. 1:28)

2. Conscience or Moral Responsibility (Fall to Flood, see Gen. 3:7)

3. Human Government (Flood to Abraham, see Gen. 8:15)

4. Promise (Abraham to Moses, see Gen. 12:1)

5. Law (Moses to the Crucifixion of Christ, see Ex. 19:1)

6. Church (Resurrection of Christ to Rapture, see Acts 2:1)

7. The Kingdom or The Millennium (Rapture to Eternal State, see Rev. 20:4).[10]

Beginning with creation and moving throughout history, each successive dispensation is characterized by a common pattern consisting of a test of faith to determine whether people will choose to align themselves with God’s economy, followed by their inevitable failure and subsequent judgment for disobedience. The Church Age, also known as the dispensation of grace, begins with the Resurrection of Christ and ends with the Rapture of the Church (a brand new concept in Christian theology at the time), followed by a seven-year Tribulation, the Second Coming of Christ, the Final Judgment, and the Eternal State of the Righteous.[11]

Since its inception to the present day, Darby’s dispensational eschatology has retained its popularity among evangelicals and Pentecostals alike. One reason for the popularity of dispensationalism is its thrilling and dramatic vision of the future, while remaining brilliantly and conveniently open-ended- enabling believers living in any generation to apply any end times signs into its system without it ever becoming outdated or irrelevant.[12] During the 1970’s, Hal Lindsey’s bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth and the movie A Thief in the Night proclaimed that the rapture was imminent based on world conditions. In 1995, dispensational eschatology was further popularized by Tim LaHaye’s Left Behind series, which made it to the big screen in 2000. Although seldom studied by ordinary believers, dispensational ideas continue to percolate in the minds of evangelicals and Pentecostals today.

B. Early Pentecostal Eschatological Thinking

Despite having an affinity with many elements of dispensationalism, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit created an obvious theological quandary for early Pentecostals.{C}[13] Dispensational theology teaches that the Pentecostal experience of Spirit baptism, speaking in tongues, and the charismatic gifts were not normative for the church age, but were only intended to inaugurate the church and ceased after the apostolic period. “Tongues and the sign gifts are to cease,” states Scofield’s commentary on spiritual gifts.[14] Moreover, dispensational views also stipulate that each dispensation, including the church age, concludes in human failure and apostasy, making any idea of a global end times outpouring of the Spirit at odds with dispensationalism. As Scofield emphasizes repeatedly throughout his text notes, “the predicted future of the visible Church is apostasy”[15] and “the only remedy for apostasy is judgment” and “catastrophic destruction.”[16] Scofield adds, “The predicted end of the testing of man under grace is the apostasy of the professing church and the resultant apocalyptic judgments.”[17] Inherently pessimistic, dispensationalism presents a powerless church with a degenerating future. With early Pentecostals enjoying the restoration of charismatic power and gifts along with increasing reports of global revival, dispensationalism became increasingly inconsistent with the Pentecostal experience. Alert to these variants, some outspoken dispensationalists judged the budding Pentecostal phenomenon as unbiblical and even sourced in the demonic; a theological wedge was widening between the two camps.[18]

Without a suitable eschatological framework to interpret the outpouring of the Spirit, early Pentecostal leaders began turning their attention to the idea of the latter rain. Originating out of nineteenth century Wesleyan-Holiness teachings, the concept of the latter rain would become the prevailing eschatological methodology for framing and validating the Pentecostal experience. Developed from a typological reading of some Scripture passages, the basis for the latter rain metaphor asserts that the chronology of the church spiritually parallels the rainfall patterns in early Palestine.[19] The term is initially found in Deuteronomy 11:10-15 where God promises the Israelites that, if they would serve him with all their heart and soul, he would give them the “early” and “latter” rain.[20]{C} According to ancient Mediterranean agricultural customs, to produce a bountiful harvest, a farmer requires rain at two critical points in the growing cycle: the early rain and the latter rain.[21] In Joel 2:23 and 28, this agricultural model is reconfigured as a prophetic metaphor to indicate the divine timeline for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the church age. The first outpouring of the Holy Spirit occurred on the day of Pentecost in Acts 2, symbolizing the “early rain” that gave life to the church. Between the early and latter rains was the long, arid period of Christendom’s apostasy and corruption during the Middle Ages. When the second outpouring of the Holy Spirit occurred at the dawn of the twentieth century, it was indicative of the “latter rain,” spiritually saturating the land in preparation for the great harvest of souls before the coming of the Lord. For early Pentecostals, the latter rain complemented their charismatic experience and affirmed the restorationist and revivalist ethos that defined the movement.[22] As opposed to dispensationalism, which rejected the possibility of an end-times outpouring of the Holy Spirit, adopting the latter rain idea provided biblical legitimacy to the Pentecostal movement and affirmed the increasing notion among early Pentecostals that they were unique participants in God’s overall eschatological timetable.[23]

Latter rain themes quickly took root in early Pentecostal publications throughout North American and came to define the eschatology of the Pentecostal movement. Many started calling the Pentecostal revival the “Latter Rain Movement”[24] and many articles began circulating with titles such as, “The Promised Latter Rain Now Being Poured Out on God’s Humble People,” and “Gracious Pentecostal Showers Continue to Fall.”[25] Seymour asserts that God “gave the former rain moderately at Pentecost, and He is going to send upon us in these last days the former and latter rain.”[26] W. C. Stevens describes Pentecost as “saturating rains” marked by “atmospheric convulsions” breaking out “here and there in various localities.”[27] Canadian pastor David Wesley Myland wrote an influential book describing the early Pentecostal movement entitled “The Latter Rain Covenant (1910).”[28] Fused with “latter rain” thematic expressions, his book relates the prevailing eschatological ethos among early Pentecostals. Believing that they were living in the final “cloudburst” of Holy Ghost power, Myland wanted everyone to get “totally soaked” by the “latter rain” which was falling so copiously from heaven.[29] Although the latter rain metaphor had its limitations, early Pentecostals used it liberally to articulate their charismatic experiences, eschatological distinctives, and their favourable position within God’s plan of redemption history.

Throughout the last century, dispensational eschatology has continued within Pentecostalism, albeit rather quietly and in the background. The eschatological doctrines of Pentecostal denominations including the AG, Church of God (Cleveland), Pentecostal Holiness Church, and the PAOC are extracted directly from dispensational teaching, but they intentionally make no mention of the word “dispensationalism”. Moreover, the word “dispensation” is noticeably absent from many key Pentecostal textbooks on eschatology, notably Stanley Horton’s The Promise of His Coming (1967). Recognizing that strict adherence to dispensationalism invalidates the Pentecostal experience, Pentecostals consider dispensationalism merely as a “helpful aid” in understanding the end times and would rather focus on the latter rain to accommodate their charismatic experience and the end times outpouring of the Spirit.[30] Unfortunately, in the 1940’s-50’s, the phrase ‘latter rain’ became associated with a splinter group in Saskatchewan and has since lost its attraction and influence in our Pentecostal eschatology.

C. Survey of PAOC Eschatological Doctrinal Changes

The following is a brief review the development of our eschatological doctrine from our formation in 1919 to our current statement.

1. May 1919, PAOC Charter

When the founding members officially formed the PAOC in 1919, they were reluctant to set up another denomination, but did so in part to protect Pentecostal doctrine.[31] That said, the PREAMBLE of the first PAOC Constitution reads: “we disapprove of making a doctrinal statement on the basis of fellowship and cooperation but that we accept the Word of God in its entirety.”[32] From the outset, Pentecostals leaders were sending a message that all are welcome and no one should be excluded because differing doctrinal opinions. It didn’t last long.

2. November, 1920 Adoption of AG Constitution

In November 1920, the PAOC joined the AG and, in doing so, adopted the statement of fundamental truths approved by the General Council of the Assemblies of God USA.[33] Within this statement are the following four eschatological doctrines:

13. Blessed Hope – The Resurrection of those who have fallen asleep in Christ, the rapture of believers which are alive and remain, and the translation of the true church, this is the blessed hope set before all believers (1 Thess. 4:16, 17; Rom. 8:23; Titus 2:13).

14. The Imminent Coming and Millenial Reign of Jesus – The premillennial and imminent coming of the Lord to gather His people unto Himself, and to judge the world in righteousness while reigning on the earth for a thousand years is the expectation of the true Church of Christ.

15. The Lake of Fire – The devil and his angels, the beast and the false prophet, and whosoever is not found written in the Book of Life, and fearful and unbelieving, and abominable, and murderers and whoremongers, and sorcerers, and idolaters and all liars shall be consigned to everlasting punishment in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone, which is the second death (Rev. 19:20; Rev. 20:1-15).

16. The New Heavens and New Earth – We look for new heavens and a new earth wherein dwelleth righteousness (2 Pet. 3:13; Rev. 21 and 22).

3. September 1927, Made in Canada

In 1927, R. E. McAlister led the charge to develop a distinctly Made in Canada doctrinal statement “separate from…the General Council at Springfield.” Intended as a “basis of unity for ministry alone” and to cover “our present needs,”[34] our first official Statement of Fundamental Truths simply inserts the following addition to the AG statement:

The rapture, according to the Scriptures, takes place before what is known as the Great Tribulation. Thus, the Saints, who are raptured at Christ’s coming, do not go through the Great Tribulation.[35]

The additional statement suggests that the General Conference wanted more clarification on the nature of the rapture than the AG statement offered.

4. August 1984, Major Revision

Changes to our current doctrinal statement were conceived on March 5, 1977 when the Standing Home Missions Committee appointed a seven-member commission to study the Statement of Fundamental and Essential Truths. This initiative was in response to a growing number of credential holders who were having difficulty giving unqualified approval to the previous statement. The Doctrinal Statement Study Committee included the following church leaders and scholars: R. M. Argue, C. A. Ratz, J. H. Faught, R. A. N. Kydd, T. Johnstone, G. B. Griffin, and G. R. Upton. At the 1984 General Conference, the house approved the new statement on eschatology that you have in front of you:

1. The Present State of the Dead

2. The Rapture

3. The Tribulation

4. The Second Coming of Christ

5. The Final Judgment

6. The Eternal State of the Righteous

Three Observations:

a) The current statement is systematized into six segments that progress chronologically and reflects the same divisions within dispensational eschatology; although no mention of dispensationalism is stated, dispensationalism certainly informed the process.

b) As this 1984 revision was initiated to satisfy a growing number of credential holders who were having difficulty endorsing the previous statement, how does the current and emerging generation of Pentecostal credential holders feel about our current statement?

c) Our official eschatological statements (past and present) excludes any mention of our Pentecostal distinctives that characterized our early eschatology; should consideration be given to a more nuanced eschatology that emphasizes our charismatic distinctives and our understanding of the end times outpouring of the Holy Spirit?

No One Righteous: Understanding Augustinian and Pelagian Views of Original Sin and their Influence on Christian Faith by William Sloos

St. Augustine Windows: Teaching about Pelagianism and Original Sin

Introduction

Cemented within church history is the renowned theological conflict between Augustine and Pelagius over the doctrine of original sin.[1] St. Augustine, considered the father of orthodox theology, taught that all humans are born contaminated by Adam’s sin, are inclined towards sinful behaviour, and are unable to obtain salvation outside of the free gift of the grace of God.[2] Pelagius, a concurrent rival of Augustine, believed his doctrine of original sin had a negative and unfortunate effect upon human behaviour, contending that it eliminates free will and removes all motivation for living a righteous life. To counteract Augustine’s teaching, he promoted the theology that humans were created free of any such determining influences and through their own righteous efforts are able to perfectly fulfil God’s commandments. Pelagius’ teachings were condemned as heresy by the Council of Carthage in 418 C.E., but his doctrines remained part of the theological undercurrent of Western theology, promoting a philosophy claiming that people are essentially good and through good works they gain divine approval.[5] In light of this historical theological conflict, the Pelagian and Augustinian views of the Adamic influence on humanity will be compared to highlight their contrasting perspectives and the impact each perspective has on Christian faith.

Pelagius and Augustine

Pelagius, born in Britain in 354 C.E., was a monk, respected theologian and spiritual advisor who moved to Rome to teach traditional European theology.[6] Though he was not ordained by the church, he was a popular and much sought after lecturer who was greatly influenced by his classical education and his reading of the early fathers of Western theology. He lived as an ascetic and was deeply preoccupied with various strands of eastern monastic literature which became increasingly evident in his teachings on Christian morality. He advocated the responsibility, obligation and the ability of all people to obey the divine commandments of the Christian faith, arguing against the deterministic fatalism of the Manichees who at the time had a relatively small, but highly influential following. When Rome fell to Alaric and the Goths in 410 C.E., he escaped with other exiles to find safety across the Mediterranean, first in the Holy Land and then in North Africa.[8] While in North Africa, Pelagius was introduced to the teachings of Augustine which led to an enduring theological confrontation.[9]

Augustine, regarded as one of antiquity’s greatest theologians, was born in 354 C.E., in Tagaste, North Africa. Greatly influenced by the reading of Cicero’s Hortensius, he joined the Manichaean religion only to abandon their teachings in favour of scepticism.[10] Admittedly leading a carnal life during his time as a student, he was converted to Christianity and baptized by Bishop Ambrose in 387 C.E. After years of retreat and study, he was ordained a priest at Hippo, North Africa and established a Catholic monastery. He synthesized and systematized Christian theology and developed his doctrine of the original sin fifteen years prior to his confrontation with Pelagius. Judging Augustine’s theories of original sin, Pelagius declared them harmful to the human endeavour of goodness which deeply disturbed Augustine and, though respectful of the virtuous monk, he set out to vigorously to defend his beliefs.[12] Considering Pelagius’ doctrines as something “no pious heart could endure”, Augustine opposed him as a heretic and charged him as an enemy of the atoning sacrifice of Christ and the grace of God.[13]

Augustinian Doctrine of the Original Sin

Augustine’s theological construction of the doctrine of original sin or concupiscence (from the Latin word concupiscentia) is derived from a literal interpretation of Scripture and his past personal experiences of sinful behaviour.[14]He relates a story about a time he stole pears from a neighbouring orchard and suggests that his reason for sinning is derived from his corrupted human nature.[15]Recalling the sinful act, he contends that his motivation was not sensual pleasure or need, nor were the pears of unusually good quality, in fact, after stealing them, he merely threw them to the swine. Concluding that his motivation was intrinsically evil, he states, “Our only pleasure in doing it was that it was forbidden.” He analyzes the root and essence of his sin and recognizes an inescapably present interconnectedness with his sinful nature, consisting of an anterior absence of God coupled with a pride that hates the truth.[17] In his transgression of the law of God, he realized that the same law that was intended to prevent sin became his primary motivation to commit sin, emphasizing his bent toward depravity. The originating grounds for this motivation, he claimed, proceeded from his childhood, which proceeded from his condition in infancy, which in turn was inherited from his parents, who inherited it ultimately from Adam.[18]

According to Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum, Augustine’s theological argument contends that humanity was originally created blameless and without any fault.[19] Adam was created in the imago Dei, upright, and in a state of good; he was given the possibility of not sinning [posse non peccare], the possibility of not dying [posse non mori], and the possibility of not losing that state of good.[20] In spite of such advantages, Adam could not persevere and chose to sin, transgressing the law of God and plunging all humanity into a new and tragic condition.[21] Augustine writes, “Thus from a bad use of free choice, a sequence of misfortunes conducts the whole human race…from the original canker in its root to the devastation of a second and endless death.” Indeed, Adam’s sin was so damnable that it resulted in the downfall of humankind, contaminating Adam’s progeny with a sinful nature from the moment of conception. The imago Dei, once perfect and whole prior to the Fall, is darkened and disabled. Human nature is under condemnation and is inclined toward evil, and non posse non peccare (not able not to sin).

In this fallen and corrupted condition, salvation is a human impossibility. The infectious nature of Adam’s sin has a disorienting force that captures the intentions of the heart, binding and bending the will away from God and all relative good.[24] Unable to achieve righteousness by their merits, sinful humanity is entirely dependent on the free grace of God through the atonement of Jesus Christ.[25] Though the sin nature resists the offer of divine grace, God sovereignly draws to himself unregenerate humanity and through the means of faith, provides remission from the power and effects of sin. Underpinning his argument with Scripture, Augustine states, “But God who is rich in mercy, on account of the great love with which He loved us, even when we were dead through our sins, raised us up to life with Christ, by whose grace we are saved.”[26] Though humanity was incapable of saving themselves, the mercy of God provided the remedy for sin and the reward of eternal life for all who believe.

Those who are regenerated through faith and have received the gift of divine grace have a restored nature, no longer enslaved to the Adamic curse. At one time unable to do good and obey the commands of God, they have been liberated from the confines of the original sin and are free to perform good works in accordance with the will of God. The motivation to do good works becomes a response rather than an obligation, a willing desire to please God because of the impartation of his grace to an undeserving sinner.

Pelagian Rejection of Original Sin

While Augustine was teaching his well constructed theology of original sin, Pelagius emerged on the scene with a radically different and controversial counter theology, strongly opposing Augustine’s doctrine of the Adamic influence upon humanity. According to Carol Harrison, Pelagius overheard a bishop in Rome quote a passage from Augustine’s Confessions discussing humanity’s incapacity to do good without the grace of God.[28] Shocked by what he heard, he argued that this premise undermined the root of human integrity and threatened the universal responsibility and effort of every human being. He reacted vehemently against this new understanding of the human nature and doctrine of divine grace, contending that this teaching served to weaken the call upon all Christians to take personal responsibility for righteous action and obedience to God’s laws.[29]

In his theological epistle to Demetrias, Pelagius asserts that God made humanity in his own image and though Adam sinned, human nature has remained essentially the same as before the Fall.[30] God has endowed each person with reason and wisdom and they possess a natural ability, not only to know what is good but actually do to it.[31] Individual choice determines whether to use these God-given abilities for good or evil. If they choose to do good, they will determine to follow the commands of God set out in Scripture and thereby achieve the purposes of God and gain his approval. If they choose to do evil and disobey the commands of God, they will incur the wrath of God and his judgment. In this way, every human being is without excuse, either on the grounds of ignorance or lack of ability since they know the good, understand it, and are able to do it, if they so will.[32]

Pelagius was utterly convinced that the will is free and there is no human defect or intrinsic evil within human nature that prevents one from choosing to do good and obey God. To suggest that God would command humans to do something they were unable to do, was effectively accusing God of being ignorant of his creation and ignorant of his own commands. Why would God put his creation in a position to fail and be eternally condemned merely because they inherited a sinful nature? To Pelagius, this would ascribe to God cruel and unrighteous attributes and make him out to be a punishment-seeker instead of a loving and holy God. Pelagius considered it inconceivable that God would ask anything of humanity, unless humanity already had the ability to achieve it.[35]

Above all, Pelagius believed that a perfect, sinless life was within human grasp; God has made it possible through his creation of the human mind, endowing it with reason and understanding and the ability to live without sin. Citing Matthew 5:48, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (NIV), he insisted that goodness, and even perfection is not only expected but achievable.[36] If humans believe they have inherited a corrupt nature and are incapable of doing good without the regenerating grace of God, they will strive for nothing and abdicate any responsibility for their evil behaviour. The idea of being born good and possessing self-determinate attributes would be the best incentive for humans to live virtuous lives and take the obligations and responsibilities of their divine purpose seriously.

As Pelagius developed his various theological tenets, there emerged the idea that human beings, by their own efforts, can fulfil all of God’s commands without committing sin. According to Milliard Erickson, the Pelagian view of salvation is essentially achieved through good works, but that in itself is a misnomer since humanity is not bound by sin to begin with and is not in need of a salvific enterprise. Salvation is, instead, a preservation or maintenance of righteousness, which is sustained through good works in accordance with the law of God. Adam and Christ are thus antithetical types for the human race. Adam, on one hand, is the prototypical example of choosing evil over good; he sinned and brought sin and death in to the world.[38] Christ, on the other hand, is the example of choosing good over evil and demonstrating to humanity what their nature is capable of accomplishing and how the commandments of God can be fully obeyed.[39] Thus, the significance of Christ is in Christ’s life, not his vicarious atonement. The teachings and example of Christ provide humanity with the pattern of a perfect and completely righteous life to emulate. If, by one’s choosing, they chose to follow the example of Christ over Adam, they would then enjoy the ultimate benefit of righteousness, eternal life.

Pelagius’ insistence on the adequacy of created human nature and the inherent ability to fulfil the will of God through good works compelled him to promote the highest moral and spiritual expectations.[41] Considering Augustine’s theory of redemptive grace superfluous to living a holy life, Pelagius wrote letters encouraging and reprimanding vowed ascetics, virgins, widows, and recent converts on how they should go about being “authentic Christians”.[42] He highlighted the importance of reading the Scriptures, keeping all the commandments, positively doing good works such as almsgiving, persevering in righteousness, preserving humility, and taking responsibility for one’s every action.[43] To those who were wealthy, he reminded them that true nobility is a matter of the soul, not of social standing and exhorted them to give their wealth away to those in material need. As an acetic himself, he led by example, observing modesty in dress, talk, food, and conduct. However, for Pelagius, calling oneself a Christian simply by avoiding what the law forbids was woefully inadequate. The true Christian is called to fulfil righteousness by actively performing good works. He states, “If you depart from evil but fail to do good, you transgress the law, which is fulfilled not simply by abominating evil deeds but also by performing good works.” In accordance to these lofty standards, human beings will be judged and either approved and welcomed into their heavenly rest or eternally condemned.

Though Pelagius’ moralist advisements sounded nothing like the work of a heresiarch, the theology that undergirded his morality was considered by others as being deconstructive to faith and godliness. Instead of Augustine’s emphasis upon the pre-eminence of love by which the Spirit of Christ graciously inspires, Pelagian looked to the fear of punishment as a strong motivation for obedience to the divine law. Motivated by fear, he contends, is a healthy motivation and leads to righteous actions. However, Pelagius’ overemphasis on the performance of good works can lead to elitism and pride and also demands the question, “how much good work is enough?” Without the promise of salvation offered in the atonement of Christ, good works alone will also inevitably lead to despair. The futility of good works even confronted Pelagius who, when writing to Demetrias about the daunting task of living a chaste life for God, remarked, “The ordering of the perfect life is a formidable matter…that is why so many of us grow old in the pursuit of this vocation and yet fail to gain the objectives for the sake of which we came to it in the first place”. Pelagius’ transparent admission demonstrates that even he, approaching the end of his life, wondered if all the good works he accomplished will result in the expected outcome.

Conclusion

The central and formative principle of Pelagianism lies in the assumption of the plenary ability of human beings. According to Benjamin Warfield, its conception brought forth an essential deism centering not on the working out of one’s salvation, but the working out of one’s perfection.[48] In the quest for perfection however, Pelagius failed to perceive the precariousness of the human condition and the effect of habit on nature itself.[49] He conceived good and evil behaviour as a series of unconnected choices absent of any continuity of life. After each act of the will, there was another act, and another, in an endless and hopeless cycle of virtue or vice.[50] Through the centuries, Pelagius’ teaching was neither uniform nor united, but it did evolve and the label “Pelagian” has become a term often loosely used to describe any doctrine deemed threatening to the primacy of grace, faith and spiritual regeneration over human ability, good works, and moral endeavour.[51] His essential philosophies remain an irresistible ideology and continue to undergird contemporary post-modern religious thinking.[52]

Augustine’s theological clash with Pelagius over the doctrine of original sin gained him the title, doctor gratiae as the teacher-defender of grace against the inimici gratiae, the “enemies of grace”.[53] The outcome of the controversy was the canonizing of the heart of Augustine’s teaching in the centuries that followed.[54] Though some elements of Augustinian’s theological system has been called into question over time (i.e. divine election, the transmission of original sin, original guilt, paedobaptism and Platonic dualism), his teachings are undeniably regarded as the theological axis around which Western theology revolves.[55] Affirmed by Calvin, Luther, and later by Wesley, his view of the doctrine of original sin has been generally received as an effective and defendable biblical treatise and remains a persuasive and influential doctrine of the contemporary Protestant and Catholic church.[56] The theological conflict between Augustine and Pelagius was not in vain, but served to sharpen the axe of biblical theology and elevate the grace of God through the cross of Christ.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Bloesch, Donald G. Essentials in Evangelical Theology. New York: HarperCollins, 1978. De Bruyn, Theodore S. “Pelagius’s Interpretation of Rom. 5:12-21: Exegesis within Limits of Polemic.” Toronto Journal of Theology 4 (1988): 30-39. Elwell, Walter A., ed. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1984. Erickson, Millard J. Christian Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1985. Ferguson, Sinclair B., Wright, David F. and Packer, J. I., eds. New Dictionary of Theology. Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press, 1988. Harrison, Carol. “Truth in a Heresy?” The Expository Times 112 (2000): 78-82. Hastings, Adrian, ed. The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Oxford: Oxford Press, 2000. Lacoste, Jean-Yves, ed. Encyclopedia of Christian Theology. Vol. 3. New York: Routledge, 2005. McGrath, Alister E., ed. The Christian Theology Reader. Third Edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2007. Melloni, Alberto, ed. Movements in the Church. London: SCM Press, 2003. Murray, John. The Imputation of Adam’s Sin. Phillipsburg: Presbyterian and Reformed Pub. Co., 1979. Rigby, Paul. Original Sin in Augustine’s Confessions. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1987. Smith, David, L. With Wilful Intent: A Theology of Sin. Wheaton: Victor Books, 1994. Warfield, Benjamin B. Studies in Tertullian and Augustine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1930.

Christ as Healer in Pentecostal Theology by William Sloos (Published under the title "Christ, Our Healer" in Authentically Pentecostal ©2010)

Introduction

As the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada (PAOC) approaches a centenary of Spirit-empowered gospel proclamation throughout Canada and the world, there is a mutual desire to rediscover its unique theological identity. Central to the shared identity of our movement is the conviction of Christ as Healer. Alongside the other four-fold theological markers of Christ as Saviour, Baptizer, and Coming King, divine healing remains an enduring, vibrant, and revitalizing feature of authentic Pentecostal faith and ministry. As we embark on this journey of rediscovering our shared identity, it appears that divine healing remains a theological staple within the emerging Pentecostal community. While discussing the shifting landscape of Pentecostal theology at the Communities of Practice (COP) at National Conference in Edmonton in 2010, the belief and practice of divine healing was identified as a defining feature of the contemporary Canadian Pentecostal church.[1] Moreover, while vigorous debate surfaced concerning other aspects of our doctrinal distinctives, divine healing continues to yield widespread incontrovertible affirmation within our fellowship.[2] Nevertheless, despite the favourable mood among Pentecostal practitioners in their ongoing support of divine healing, there remain a number of significant issues with the theology of divine healing that require our attention. Following a brief historical reflection of divine healing in early Pentecost, we will examine three critical issues: 1) the double atonement healing theology, 2) the relationship between medical science and divine healing, and 3) the nature and function of the gift of healing. Intended to further our national conversation about divine healing within the Canadian Pentecostal context, this paper will conclude by proposing a way forward in our shared theological journey.

Historical Reflection

To sufficiently grapple with our Pentecostal identity as a movement, it is essential that we listen to the voices of our early pioneers and learn from our past. Grant Wacker, in his seminal monograph on the social context of early Pentecostals, declares, “if tongues defined the movement, healing gave it life.”[3] In his assessment, divine healing was the dramatic visible manifestation of Christ’s conquest over the enemy. While testimonies of Spirit-baptism were relatively analogous, divine healing testimonies tallied in the thousands and ranged from “runny noses dried up to dead bodies raised to life – and everything in between.”[4] Testimonies were proclaimed with the vividness of New Testament vocabulary or the simple prose of a medical report, yet all were punctuated with unspeakable joy and enthusiasm for the modern-day restoration of the apostolic gifts. “Canes, crutches, medicine bottles, and glasses are being thrown aside as God heals,” proclaims William Seymour.[5] Ellen Hebden writes, “Cases of asthma, fever, rheumatism, lung troubles, drug habits and other diseases that are common to all humanity have been cured by divine power.”[6] “Jesus is our family doctor” claims Zelma Argue, “No case is either too small or too difficult for Him.”{C}[7] So persuaded that Christ was able to heal every sickness and disease, early Pentecostal periodicals repeatedly exhorted believers to decline all medical means and “take the Lord as your healer.”[8]

Within this spiritually-charged atmosphere, divine healing became one of the central underpinnings of the embryonic Pentecostal movement. Through these early years, a prevailing narrative began to emerge that outlined the increasingly familiar testimonial pattern of the lives of Pentecostal believers: “converted,” “sanctified,”[9] “healed,” “baptized with the Holy Ghost,” and “has a call to a foreign field.” By the 1920’s, divine healing became entrenched within the Pentecostal consciousness as one of four-fold doctrinal pillars of the faith. Popularized by Canadian Aimee Semple McPherson, the slogan, “Four Square Gospel,” first appeared on the cover of The Bridal Call in September 1922, declaring Jesus as Divine Healer.[10] By April 1930, the cover of The Pentecostal Testimony began declaring “Jesus, Saviour, Baptizer in the Spirit, Divine Healer, Coming Lord.”[11] By the end of the decade, editor D.N. Buntain added this motto under the banner of the Testimony: “Carrying the Testimony of Salvation from Sin, Healing for the Body, Baptism of the Holy Ghost, and the Return of Our Lord.”[12] The concept of Christ as Healer was thoroughly cemented in the hearts and minds of Pentecostal people and, despite the diversity within the contemporary ecclesial context, divine healing continues to characterize the prevailing theological and devotional ethics of Canadian Pentecostalism.

Current Challenges

a) The Double Atonement Healing Theology

Despite the faith and fervour among early Pentecostals that proclaimed Christ as Healer, the theology of divine healing has had an unattractive underside that has persisted to this day. Adopted by early Pentecostals was the soteriological notion that salvation and divine healing is assured in the atonement of Christ – a supposed double atonement.{C}[13] Key biblical texts supporting this doctrine were Is. 53:4-5, “by his stripes we are healed,” and Mt. 8:14-17 “Himself took our infirmities, and bare our sicknesses.”{C}[14] Advocates contended that these texts connected the act of healing to the efficacy of Christ’s death on the cross; that through Christ’s death, He triumphed over Satan and conquered sin and sickness, thereby making salvation and healing equally and universally available to all believers. Leaving little room for the sovereignty of God, the natural laws of nature, or the reality that we live in a fallen world, the appropriation of salvation and healing was completely dependent on believers to exercise sufficient faith in Christ’s atonement. Those who were unable to receive their healing were largely considered to have inadequate faith to apprehend what Christ had already secured for them at Calvary.{C}[15]

Embracing such a rigid healing theology generated considerable tension among those who failed to find relief from their suffering. Articles would surface that would fault suffering believers for their existing ailments and handicaps, such as a 1936 article in The Pentecostal Evangel entitled “Why Many are Not Healed,” which outlines numerous reasons why suffering believers fail to apprehend their healing.[16] Regrettably, the article ran again twenty years later, only this time it included a picture of a man languishing in a wheelchair- his physical disability persisting due of his lack of faith.[17] Reprinting articles was not uncommon in Pentecostal periodicals, reprinting this article simply demonstrates the enduring preoccupation with this flawed theory. This theology also generated tension among Pentecostal missionary families who reached foreign shores trusting in Christ’s atonement to protect them from sickness and disease. When their loved ones died from malaria and other diseases, missionaries struggled to explain such devastating circumstances, often insisting that their loss must have been the will of God.[18] Furthermore, when early Pentecostal preachers and teachers of this double atonement theology later suffered age-related illnesses and diseases, propagation of their once triumphant healing theology suddenly grew silent.[19] Unfortunately, remnants of the double atonement theology persist today and some Pentecostal believers continue to maintain that Christ has already secured their healing at Calvary- all that is required is to claim their healing through the exercise of sufficient faith (for some, even to the exclusion of medical means). Although we believe that every good gift from God is mediated to us by virtue of Christ’s work on the cross, we cannot ignore the fact that we live between two ages – the present evil age and the age to come. Mystery exists between the brokenness of a fallen world and the in-breaking of God’s future full redemption. In the words of William Menzies, “divine healing is but a foretaste of the ultimate transformation we await.”[20]

b) The Relationship between Divine Healing and Medical Science

Emerging from our shared Pentecostal history has been a persistent suspicion concerning the role of medical science in the lives of believers. The rousing tune “Who’s report do you believe? We shall believe the report of the Lord,” is often interpreted to triumphantly declare God’s good report over and against the dire report of our family physician. Some Pentecostals have embraced the romantic notion that the early believers were so faith-filled that they rejected all doctors and drugs and simply believed for their miracle. Largely overlooked is the fact that during the early days, medical science was exceedingly primitive. A round of the calomel (currently used as an insecticide) and a dose of castor oil along with some orange juice was given for stomach aches.[21] A remedy for arthritic pain was a total dental extraction on the mistaken premise that debilitating illness lurked in the mouth. If this was unsuccessful, doctors would recommend gold injections or bee stings. If you were unfortunate enough to have a skin infection, the physician may advise the application of a freshly killed chicken since cow manure was too messy. The same medical needles and syringes to treat livestock were also used to inoculate children, occasionally resulting in their deafness (likely due to the antibiotic streptomycin which can cause hearing loss). During an epidemic of diphtheria in New York in the nineteenth century, two out of three patients treated by a physician died, in contrast to only two of nine patients treated only with “ice packs and prayer.”[22] Too often we are ignorant to the harsh realities of the early years and simply admire the faith of early Pentecostals when in fact many likely recuperated from their illnesses by simply avoiding the doctor. In the contemporary context, we have been exceedingly privileged to live in a technologically advanced society dedicated to health and wellness. As we exalt Christ as Healer and pray for the sick and suffering, we recognize that divine healing is not in conflict with medical science but functions cooperatively, manifesting through prayer and the wisdom and skill of medical practitioners.

c) The Nature and Function of the Gift of Healing

Another area of discussion within the theology of divine healing is the notion that someone can possess the “gift” of healing. According to Paul, some are given the gifts of healing (1 Cor. 12:9), indicating that some believers seem to receive a greater proclivity to heal the sick. With this in mind however, Ronald Kydd makes several insightful observations about the nature and function of the gift of healing.[23] First, the gift of divine healing flows out of the mystery of God and can not be formulated, categorized, and marketed. Jesus himself did not follow any set blueprint or formula- the only evidential pattern in Jesus’ healings was the presence of Jesus Himself. Those who possess the gift of healing and claim to comprehend its mysteries are misguided at best. Second, the stereotypical healer does not exist. From the high energy of Oral Roberts to the soft spoken William Branham, from the flamboyant Kathryn Kuhlman to the former jazz musician John Wimber, there is not one like the other. Modelling a healing ministry after a personality is undoubtedly freighted with pitfalls. Third, despite the claims of healers and their supporters, reports of divine healings are often overstated. Many people have a difficult time controlling their enthusiasm, especially in the midst of an atmosphere supercharged with faith. Proper medical verification and reporting are rare and even rarer are those who admit they were not healed, creating confusion between genuine healing and what may be merely pleasing to the imagination. Finally, possessing the gift of healing is not necessarily reflective of doctrinal correctness. Advocates of divine healing have often treaded on the fringes of orthodoxy with extra biblical claims and behaviours. Within this seemingly precarious milieu of divine healing, possessing the gift requires a considerable measure of maturity, responsibility, and humility. However, as the gift is appropriately exercised and evaluated within the Body of Christ, excesses are minimized, and doctrinal soundness is maintained, the operation of the gift of healing can be a catalyst for the rediscovery of the fullness of the Holy Spirit in the local church. Moreover, as healing ministries within the charismatic movement have demonstrated, the gift of healing is not just confined to physical healing, but also provides inner healing, deliverance from emotional suffering, and the restoration of the whole person.[24]

A Way Forward

To further our national conversation about divine healing within the Canadian Pentecostal context, there are three things I would like to propose for consideration. First, there is a need for the development of a thorough and practical theology of suffering. Within our churches, a prevailing narrative of triumphalism exists that minimizes the harsh realities of sickness and suffering. Largely neglected by Pentecostals who have traditionally viewed suffering and the Spirit-filled life as incompatible, the Luke-Acts paradigm paints an entirely different picture. A consistent Christological and apostolic theme, suffering was an ever present reality in the early church and an expected consequence of Spirit-empowered gospel proclamation. Within the contemporary context, emphasis on the triumph over suffering resonates from songs and sermons but there is little room for prayerful dialogue concerning the mystery of suffering. As the Holy Spirit relates to miracles, signs, and wonders, the Spirit also relates to suffering and weakness; living in the shadow of the cross and in the power of the Spirit is not mutually exclusive but is rather the actualization of more complete representation of the presence of Christ in the lives of believers.[25]

Second, the theology and practice of divine healing must remain centred on Christ. According to Francis MacNutt, the existing practice of divine healing centres far too much on the individual.[26] For nineteenth century Lutheran theologian Johann Christoph Blumhardt, locating divine healing solely on the person of Christ was essential to his ground-breaking healing ministry.[27] After praying unsuccessfully for two years for the deliverance of a demon possessed woman, Blumhardt began to fast in accordance with the instructions of Jesus that some demonic forces can only come out by prayer and fasting. One night, while interceding for the woman, she suddenly shrieked, “Jesus is victor! Jesus is victor!” and she immediately received complete deliverance.[28] For Blumhardt, this experience demonstrated that the all-encompassing work of Christ was sufficient for healing. While this dramatic deliverance launched Blumhardt into the spotlight of the emerging divine healing movement, he never held a healing service, never prayed for lines of waiting people, never looked for instantaneous healing, never hesitated to recommend a physician, and never felt that he had to prove anything about himself or his ministry. For Blumhardt, Jesus was the source, means, and victor over all manifestations of evil and is completely capable of dealing decisively with sin and its consequences. In the contemporary Pentecostal context where gifted personalities are routinely elevated and celebrated, Blumhardt’s Christocentric healing theology and praxis is worthy of further study.

Finally, recovering the missional nature of divine healing is essential to fulfilling our mandate as a national fellowship. For Jesus, the locus of divine healing was not confined to the temple or synagogue, but abundantly disseminated among the populace. An essential feature of His mission was the physical healing of sick and suffering people. Describing the missional nature of Jesus’ healing ministry, distinguished church historian Adolph von Harnack writes:

The first three gospels depict him as the physician of soul and body, as the Saviour or healer of men. Jesus says very little about sickness; he cures it. He does not explain that sickness is health; he calls it by its proper name, and is sorry for the sick person. There is nothing sentimental or subtle about Jesus; he draws no fine distinctions, he utters no sophistries about healthy people being really sick and sick people really healthy. He sees himself surrounded by crowds of sick folk; he attracts them, and his one impulse is to help them.[29]