Leadership Papers

“In matters of style, swim with the current.

In matters of principle, stand like a rock.”

An Ecclesial Paradigm for the Post-Modern Culture: The Missional-Community Model by William Sloos

Issue and Objectives

Throughout history, Christianity has been shaped by its surroundings and is always unavoidably contextualized within the parameters of the culture in which it exists. Within the contemporary post-modern culture, the church is being influenced by a heterogeneous, complex social framework that challenges absolute truth and extols tolerance and pluralism. For the church to effectively proclaim the timeless message of the gospel in this disjunctive cultural landscape, the church cannot continue to function according to the one dimensional and unbalanced ministry models that have emerged in the modern age. The church must recover its essential nature as a missional community fully engaged in the Missio Dei, the mission of God to reconcile fallen creation. Only when the church recaptures its authentic biblical identity and reconfigures its ministry and organization accordingly, can the church effectively impact the culture with the redemptive reign of Christ through the power of the Holy Spirit.

This paper proposes a biblically-based ecclesial paradigm that can effectively communicate the message of the gospel in the contemporary post-modern context. Following a brief examination of the culture and current ministry models of congregational mission, the New Testament understanding of the nature of the kingdom of God will be reviewed and serve as the foundation for the development of an ecclesiology that embraces the church’s core identity as a missional community. Subsequently, the proposed ecclesial paradigm will examine its ability to interact with the post-modern culture and explore its effectiveness in sharing the message of the gospel. This study will conclude by discussing possible obstacles and assets in its relationship with the current context.

The Contemporary Post-Modern Context

The term “post-modernity” was articulated back in the 1930’s and was used in reference to a new style of architecture, essentially as a reaction against modernism. The contemporary post-modern culture began taking shape in the late part of the twentieth century as a reaction to modernist assumptions and worldviews. Though there is some continuity with modernism, post-modernist ideology is essentially a rejection of the emancipatory role of reason and science and the dismissal of any universal or absolute truths (Lecture Notes Week 5). Meta-narratives that previously explained the knowledge and experience of the modern culture have been abandoned. Post-modern thinking is predominantly pessimistic, challenging the idea that history is progressing and that all human problems could eventually be solved. In post-modern culture, knowledge is socially conditioned and constructed within communities, determined by what is real at the local level as opposed to a broad-based, artificially imposed order. No single account of reality is privileged, but all opinions are equally valid and respected. Human identity or selfhood is realized within the world and is perceived through the feelings, senses, and emotions (Lecture Notes Week 5). Since all truth is subjective and based on individual belief systems, the post-modern person is in constant search of new experiences that bring meaning and value to their existence. This pursuit has created a culture of citizen-consumers where everything is for consumption, including meaning, truth and knowledge (Sampson, Reading Packet).

Confronted with this dynamic and rapidly changing environment, the church is faced with the challenge of communicating the gospel in this uncharted context. However, before the church can adequately minister in the post-modern culture, the church must first address its own imbalances, specifically the distorted understanding of its nature, ministry and organization.

Current Ministry Models of Congregational Mission

Within contemporary church culture there exists an unbalanced missional understanding between evangelism and social action. One side, namely the evangelistic or sanctuary orientation, majors almost exclusively on evangelism and considers social action insignificant to the church’s perceived divine mandate. Derived from a dispensational theology, which contends that society will inevitably degenerate until the return of Christ, these churches believe the single most important biblical mission of the church is to save souls (Sider 34). This distorted understanding of the essential nature of the church neglects the cry of the poor and oppressed and overlooks the need for justice, peace, and freedom throughout the world. Otherworldly in nature, this skewed perspective stresses salvation for a future world, makes a clear distinction between religious and secular spheres, accepts existing social structures as they are, and objects to “sinful” lifestyles as opposed to the immorality of the culture (Lecture Notes Week 9). This orientation is inherently flawed and one dimensional, centering on the justification and regeneration of individuals rather than the dawning messianic kingdom where all areas of life are to be reconciled to God through the community of Christ (Sider 34).

On the other side of the ecclesiastical spectrum is the civic or activist orientation which disregards evangelism and focuses squarely on social action at varying degrees. Common features of this model stress the establishment of the kingdom of God in society, general concern for the welfare of all people, ecumenical cooperation, involvement in public affairs, and social awareness and activity (Lecture Notes Week 9). Compared to the evangelistic model, the civic or activist model is considered a worldly approach, void of the biblical view of salvation; however both models are one dimensional in scope and fail to grasp the true holistic mission of the church. Devastating to the church’s witness and credibility, each model uses the other’s one-sided approach to justify its own continuing lack of balance, and in doing so, continues to present only a shadow of the true transforming message of Christ (Sider 17).

Consequently, these current ministry models of congregational mission have strayed from the paradigm of the New Testament church, causing the church to be defined by its function instead of its mission. No longer anchored to the purposes of the kingdom of God, the current church is laden with bureaucracy, saturated with individualism, and has little time or desire for prayer and the leading of the Holy Spirit. Evangelism is far down on the list of priorities, buildings take up enormous time and resources, financial debt has arrested effective ministry, and the Christian lifestyle is almost indistinguishable from that of non-Christians (Lecture Notes Week 10). Ministries such as worship, education, and service are typically assumed by professionals and missions has been relegated to a relatively minor part of the larger ecclesiastical structure. Without an awareness of the core identity of the church there is no missional ownership among the body, creating a consumer mentality focussed on the rights and privileges associated with the membership, not on a covenantal commitment to the community and its values (Van Gelder 67). Loosed from its missional moorings, the church has drifted away from its essential nature and has become disconnected from the intrinsic relationship between the life and ministry of the church and the nature of the kingdom of God (Lecture Notes Week 10).

The Kingdom of God

The New Testament understanding of the kingdom of God not only illustrates how both evangelism and social action can and should partner together as a holistic ministry model, but more importantly, identifies the essential nature of the church, providing a biblical paradigm in which to define a proper ecclesiology. At the very core of Jesus’ life and ministry is the message of the kingdom of God. Matthew 4:23 states, “Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, preaching the good news of the kingdom, and healing every disease and sickness among the people.” This proclamation of the dawning of the kingdom of God is alluded to 122 times in the Synoptic Gospels and defines Jesus’ mission and purpose for coming to earth. Not just a theological concept, the kingdom of God is before all else a person with the name and face of Jesus of Nazareth, the image of the invisible God who, through the power of the Holy Spirit, declared and demonstrated the signs of the kingdom to a broken and fallen world. Central to the kingdom is the apostolic message of the gospel or “good news” that is not only confined to a spiritual salvation, but encompasses a holistic framework including social concern for the poor, weak, and marginalized (Sider 51, 59).

To understand the holistic nature of the kingdom of God, an understanding of the following four components is required: individual, corporate, vertical, and horizontal (Sider Chapter 5). First, the kingdom of God invites individuals to receive salvation through faith in Christ who, through his sacrificial and atoning death on the cross, forgives their sin and transforms every area of their lives. Not only are individuals reconciled to God, they also become new creatures in Christ, no longer enslaved by the old nature. Second, the kingdom of God has a corporate nature consisting of the redeemed Spirit-filled community, the body of Christ, which manifests the fruit of the kingdom of God within its common life and shared ministry (Lecture Notes Week 9). Through this community, the principles and values of the kingdom of God are actualized in the midst of everyday life in word and deed. Third, the kingdom of God is vertical, that is, it involves living in right relationship to God. Through a personal and growing relationship with Christ, values, actions, and relationships are transformed and sinful behaviours are replaced with the love of God and the power of the Holy Spirit. Finally, the kingdom of God is horizontal, where people who have been reconciled to God and each other, carry the message of abundant life, wholeness, and reconciliation into a broken and fallen world in response to the redemptive reign of Christ. In these four aspects, the kingdom of God is viewed as a multi-dimensional integration of the holistic nature of the Missio Dei to reconcile all of creation (Sider Chapter 5).

Within this four dimensional framework, the church is called to be the visible expression of the kingdom of God and fulfil its holistic mission of reconciliation on the earth. Instead of existing for its own purposes, the church is designed to exist as the redeemed community of Christ in the world, proclaiming salvation, living in right relationship with God, and carrying the holistic message of reconciliation to all creation. Instead of emphasizing only one aspect of the kingdom, the church must embrace every aspect of the kingdom; instead of being defined only by its functions, the church must be defined by the mission of the kingdom. The mission of the kingdom is the mission of the church. Recognizing that the kingdom of God cannot be separated from the mission of the church, the church must recover its essential nature to effectively communicate the gospel to the post-modern culture.

The Missional-Community Model

Based upon the nature and mission of the kingdom of God, the development of an ecclesial paradigm for the post-modern context should centre around two essential components: 1) the church as missional and 2) the church as community.

First, the missional nature of the kingdom of God is essential to the understanding of the church. According to Lesslie Newbigin, the common belief that the church can exist without being missional involves a radical contradiction of the truth of the church’s very being. He insists that no recovery of the true wholeness of the church’s nature is possible without a recovery of its radically missionary character (Lecture Notes Week 9). For the church to be the true church, its very essence must reflect the missional nature of the kingdom of God. Church and mission are not two distinct entities, as is often the case in current ministry models, but are fundamentally interrelated and must be merged into a common ecclesiology that pervades every area of the church’s nature, ministry, and organization (Van Gelder 31).

When the missional nature of the kingdom becomes the essential nature of the church, everything the church does will reflect its missional nature (Van Gelder 37). The ministries of the church will no longer simply be routine religious activities that take place throughout the church calendar, but will be organized around a deliberate and intentional framework that reflects the missional nature of the church. The message of the gospel will be proclaimed for the salvation of individuals, the redeemed community will mutually experience the love of God and the presence of the Holy Spirit, believers will engage in a right relationship with God through the cross of Christ, and the message of abundant life, wholeness, and reconciliation will be brought into a broken and fallen world. Only when the missional nature of the church is restored, will the holistic ministry of Jesus resume in the power of the Holy Spirit, transforming lives spiritually and socially until the consummation of the kingdom.

Second, the church not only must regain its missional nature according to the biblical principles of the kingdom of God, but must also exist in community. Contrasting current ministry models, the church is not just a building, a set of organized programs, or even a collection of individuals. The church is not a legitimization of authority lodged in an institution, nor is it an exclusive religious society segregated from the evil world around it. Instead, the church is designed to be an active fellowship of reconciled relationships, interacting and partnering together through shared values and mutual experiences. The biblical imagery describing the church reflects its communal nature with words such as, “people of God”, “temple”, “body of Christ”, and “communion of the saints”. These images develop a common theme highlighting the interconnected and interrelated nature of the church. At its very core, the church was designed to be a spiritual and social community made up of people who are reconciled to God and one another (Van Gelder 108).

Within this paradigm are four critical components that define the type of community the church is to embody. First, the church is to be a community of Christ, representing his life and ministry through the proclamation of the gospel to the world. Second, the church is to be a community of the cross, shaped by the suffering of Christ. Just as Jesus suffered and died to liberate the world from the idols of power, so the redeemed community is also called to endure suffering to liberate people from evil, injustice, and oppression. Third, the church is to be a community of the resurrection, living in the resurrection power of the Holy Spirit and experiencing Christ’s victorious reign over death and the forces of evil. Lastly, the church is to be a community of fellowship, befriending the sinners and tax collectors of this current age with the authentic love of Christ (Lecture Notes for Week 8). In these four aspects, the community embodies the fullness of the person and work of Christ to the world.

The Missional-Community Model in the Post Modern Context

Communicating the message of the gospel in the post-modern context is fundamentally different from sharing the gospel in the modern context. A blueprint for evangelism in the post-modern culture requires a relational approach, emphasizing the value of genuine friendship and trust. No longer persuaded by traditional evangelistic sermons or intelligent apologetics, post-modernists are largely attracted through non-confrontational methods. Instead of presenting a tract or being handed a Bible, they wish to see Christianity authentically lived out on a consistent basis before they are willing to explore it for themselves. Keenly aware of frauds, they consider the character and personal integrity of the messenger equally important as the message. Uninterested in meaningless forms and traditions, they are looking to experience real meaning in their personal lives and participate in something that challenges them at the core of their being (Lecture Notes for Week 10).

The proposed missional-community model, as it exemplifies the essential nature of the kingdom of God, is an ecclesial paradigm that can effectively communicate the gospel in the distinctive cultural landscape of post-modernity. Through the church’s missional nature, the church presents a holistic gospel, not only concerned about spiritual salvation, but focussed on the reconciliation of the whole person. The missional church also provides the opportunity for an authentic experience of the person of Jesus Christ through the power of the Holy Spirit. Unbound by religious customs and traditions, the missional church connects the post-modern seeker with God through a variety of meaningful functions such as worship, discipleship, fellowship, service, and prayer. Additionally, the missional church calls people to participate in something larger then themselves, namely the kingdom of God which offers a challenging adventure to take the message of spiritual and social reconciliation into the world (Lecture Notes for Week 10).

If the missional aspect of the church provides the believing element of conversion, the church’s communal nature provides the belonging and behaving elements (Lecture Notes for Week 10). The communal church not only accepts everyone with the love of Christ, but emphasizes the importance of developing authentic relationships and actively works at connecting people in meaningful ways. The communal church embraces non-confrontational methods of ministry and, though uncompromising in its beliefs, welcomes open discussions and does not sit in judgment of opposing ideas. Believing in living a transformed life according the gospel, the communal church works at strengthening people in their relationship with God and helps them personally experience the transforming nature of the gospel in their daily life. Through both the missional and communal nature of the church, the gospel can find favour in the post-modern culture and can be an effective witness of the kingdom of God.

Obstacles and Assets of the Missional-Community Model

As with all ecclesial paradigms, the missional-community model will encounter obstacles in its ministry and function. First, due to its relational nature, there may be a tendency to diminish the cost of discipleship among new believers. Since developing interpersonal relationships are a priority, the danger of sacrificing discipleship for the sake of maintaining relationship does exist. Second, dealing with interpersonal conflict also presents a challenge. Interacting with people at a deeper relational level than other modern ecclesial models will inevitably lead to some conflict. The ability to resolve conflict will be paramount for the missional-community model. A third obstacle is the challenge of addressing criticisms stemming from supporters of modern ecclesial models who emphasize evangelistic or social action approaches to ministry. Coming from other traditions, they may perceive the missional-community model to be too tolerant, too seeker-oriented, or too far removed from their perception of a proper understanding of the church. Despite these challenges, the missional-community model remains an effective ecclesiology for communicating the gospel in the post-modern context.

The assets of the missional-community model centre on its compatibility with the post-modern context. Not only connecting people to a transforming personal relationship with Jesus without the baggage of modern religiosity, the missional-community model fosters authentic relationships with others and provides meaningful experiences with God through the power of the Holy Spirit. Instead of being passive and spectator-oriented, the missional-community model calls for active participation in the global Missio Dei, providing a shared purpose in holistic transformation. Though considerably different from current modern ecclesial models, the missional-community model can effectively communicate the message of the gospel in the contemporary post-modern culture and see lives radically transformed for the kingdom of God through the redemptive reign of Christ.

The Baptism in the Holy Spirit and the Emerging Church: Theological Foundations and Practical Applications by William Sloos

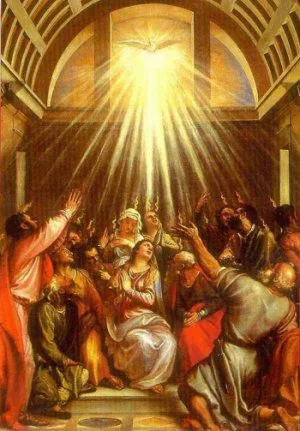

The Day of Pentecost, Acts 2

Introduction

According to the teachings of Scripture, the baptism in the Holy Spirit is an experience that empowers and equips believers to be witnesses of the resurrected Christ. Prophesied in the Old Testament, Joel anticipated an outpouring of the Holy Spirit on all people that would produce prophetic speech and spiritual manifestations. In the Gospels, Jesus teaches the disciples that the baptism in the Holy Spirit is an immersive and empowering event that is received through prayer. Initially occurring on the day of Pentecost, the Acts narratives record how Spirit-baptism is an experience subsequent to and separate from salvation, initially evidenced by speaking in tongues, and available to all believers. Considered an essential experience in the discipleship journey, the baptism in the Holy Spirit was continually demonstrated in the early church, empowering and equipping the disciples for ministry and fuelling their missionary endeavours.

Endeavouring to rediscover the essential message of Christ and share it with the post-modern generation, the emerging church has become a significant movement within the Christian community over the past twenty years.[1] Prophetic, post-modern, and praxis-oriented, the emerging church counters the methodologies of the traditional church and embraces a missional ecclesiology that actively participates in spiritual formation and community transformation.[2] Considering themselves to be post-evangelical, they refuse to be identified with the religious ideologies that dominate contemporary evangelicalism, preferring to be viewed as an authentic community of Christ followers.[3]{C} Striving to live out the life and mission of Christ within the post-modern culture, the emerging church actively participates in the redemptive work of God through social justice, helping the poor, and advocating for the marginalized in their communities.[4]

Following the example of the early church, introducing the experience of the baptism in the Holy Spirit to the emerging church can be a transformative experience. Since the nature of Spirit-baptism is oriented towards mission, embracing the experience can supernaturally empower and equip the emerging church to fulfil their missional endeavours. This paper will argue that the experience of the baptism in the Holy Spirit is grounded in the teachings of Scripture and can empower and equip the emerging church for effective ministry in the post-modern generation. Divided into two parts, the first part of the paper will explore the theological foundations for the baptism in the Holy Spirit and the second part of the paper will practically apply the principles of Spirit-baptism to the emerging church within an urban Canadian context.

Part 1: Theological Foundations for Spirit-Baptism

The following study will examine the theological foundations for the baptism in the Holy Spirit by reviewing the Old Testament prophecies of Ezekiel and Joel, the pre- and post-resurrection teachings of Christ, and Luke’s account of the early church in the Acts narratives.

1. Old Testament Prophecies about the Holy Spirit

Climaxing on the Day of Pentecost, the promise of the coming of the Holy Spirit was prophesied centuries earlier in the Old Testament. Although there are many references to the Holy Spirit in the Old Testament, two specific passages in Ezekiel and Joel are particularly important in understanding the unique roles the Holy Spirit will fulfil in the lives of New Testament believers.[5] The first passage is in Ezekiel 36:25-27, which speaks prophetically about how God will cleanse his people from their sins, give them a new heart and also a new spirit. To effect this spiritual transformation, the Lord states, “I will put my spirit within in you, and make you follow my statues and be careful to observe my ordinances” (NRSV). Through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, God promises to inhabit his people and guide them in righteousness. In this passage, the function of the Holy Spirit anticipated by Ezekiel refers to the New Testament concept of regeneration and finds affirmation in Paul’s writings when he explains how the Holy Spirit dwells in all believers (Rom. 8:9, 14-16; 1 Cor. 6:19).

Notably different from the Ezekielian prophecy, the second passage concerning the coming of the Holy Spirit is found in Joel 2:28-29.{C}[6] Without any references to indwelling people or affecting inner transformation, God promises: “I will pour out my spirit on all flesh.” Echoing Moses’ wish “that all the Lord’s people were prophets, and that the Lord would put his spirit on them” (Num. 11:29), Joel’s prophecy reveals God’s plans to impart his Holy Spirit to all people, not just prophets, kings, and judges. Resulting from this divine outpouring, the prophecy indicates that people will engage in prophetic speech and other supernatural manifestations. Following the Day of Pentecost, when the disciples were “filled with the Holy Spirit,” (Acts 2:4) Peter repeats Joel’s prophecy with the understanding that the prophetic announcement is fulfilled and the outpouring of the Spirit is for everyone. The significant difference between Ezekiel’s prophecy which declares that the Holy Spirit will indwell people and Joel’s prophecy which proclaims that the Holy Spirit will be poured out upon people clearly indicates that the Holy Spirit will have a dual function in the lives of new covenant believers.

2. Jesus’ Teaching on the Coming Holy Spirit

Despite the unprecedented and dramatic descent of the Holy Spirit on the Day of Pentecost, the event did not come as a surprise to the waiting disciples. According to Roger Stronstad, the gospel of Luke demonstrates that Jesus had been instructing the disciples concerning the outpouring of the Holy Spirit before and after his resurrection.{C}[7] Prior to his resurrection, Jesus’ first recorded incident of teaching about the Holy Spirit is in the context of prayer. “If you then, who are evil know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him” (Lk. 11:13). This text suggests that Jesus considers the Holy Spirit a gift that is given by the Father to those who ask. Not coincidently, when the Holy Spirit descended on the Day of Pentecost, it was preceded by the prayers of the disciples.

The second pre-resurrection teaching occurs when Jesus informs his disciples that the Holy Spirit will be with them and counsel them when they face persecution. Encouraging the Twelve, Jesus declares, “do not worry about how you are to defend yourselves or what you are to say; for the Holy Spirit will teach you at that very hour what you ought to say” (Lk. 12:12). Reaffirming this promise just before his death, Jesus tells the disciples, “I will give you words and wisdom that none of your opponents will be able to withstand or contradict” (Lk. 21:15). Following the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, Jesus’ promise finds fulfilment on several occasions throughout Acts. Peter’s questioning by the Sanhedrin about his preaching is one illustration. Luke notes that he was “filled with the Holy Spirit” and, despite being “ordinary” and “uneducated,” he spoke with “boldness” (Acts 4:8-13). Through Jesus’ teaching and later fulfilment, Luke shows how the baptism in the Holy Spirit equips and empowers believers to bear witness to the resurrected Christ, particularly within the context of a hostile environment.

According to Stronstad, Jesus makes three post-resurrection promises concerning the Holy Spirit that are specific and directly relate to the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost.[8] The first of these promises unveils Jesus’ intention to endue his disciples with supernatural power in advance of their mission to witness to the resurrected Christ. “I am sending upon you what my Father promised,” Jesus declares, “so stay here in the city until you have been clothed with power from on high” (Lk. 24:49). Highlighting the unity of the Godhead in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, Jesus informs his disciples that the Father’s gift of the Holy Spirit is sent through the Son with the expressed purpose to fill them with spiritual power. Commanding them to wait in Jerusalem for the promised gift, Jesus intends to empower his disciples with the same power that anointed his ministry to liberate and redeem fallen humanity (Lk. 4:14).[9]

The second post-resurrection promise indicates that the coming of the Holy Spirit will not just be an empowering event, but also a baptismal event. Recalling John the Baptist’s earlier prophecy that Jesus would “baptize with the Holy Spirit and fire” (Lk. 3:16) Jesus says to his disciples, “For John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now” (Acts 1:4). With the baptism of fire reserved for eschatological judgment, Jesus describes the promised outpouring of the Holy Spirit as an immersive experience that will plunge the disciples into the life of the Holy Spirit.

Though implicit in the previous promises, Jesus’ third and final promise explicitly reveals the purpose of Spirit-baptism for the disciples. Jesus states, “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). Emphasizing the missional purpose of the outpouring of the Spirit, Jesus explains to the disciples how the Holy Spirit is their source of power that will enable them to witness to the resurrected Christ in the world. Following the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, the disciples immediately begin experiencing the enabling power of the Spirit as they speak in tongues and declare the mighty works of God to the amazement of an multinational crowd that had gathered outside the upper room (Acts 2:4-11).

3. The Nature and Characteristics of Spirit-Baptism in the Acts Narratives

Building on the prophecies of the Old Testament and the words of Christ, attention will now concentrate on the nature and characteristics of Spirit-baptism within the Acts narratives.

3.1. Subsequence and Separability

First and foremost, the baptism in the Holy Spirit is an experience subsequent to and separate from conversion. Although some scholars contest this argument suggesting that there is not a subsequent experience after conversion, but the gift of the Holy Spirit is only given at regeneration, these claims are not convincing against the backdrop of the Lukan narratives.{C}[10] When the Holy Spirit was poured out upon the waiting disciples on the day of Pentecost, it is widely accepted that the disciples had already repented for their sins and entered into a new life in Christ. Jesus alludes to their conversion prior to Pentecost when he tells the seventy-two to “rejoice that your names are written in heaven” (Lk. 10:20).[11] Moreover, when Peter and John were sent to the Samaritans to pray that they might receive the Holy Spirit, the text clearly states that the Samaritans had previously “accepted the word of God” and had been “baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 8:15-16), indicating they were regenerated prior to their baptism in the Holy Spirit. Furthermore, three days after Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus, Ananias prayed that he would be “filled with the Holy Spirit” (Acts 9:17), emphasizing the subsequent and separate experiences of regeneration and Spirit-baptism. According to David Lim, “The Early Church expected a separate, distinct, and vital experience of an enablement of power in the Holy Spirit.”[12] Following the Pentecostal outpouring, it appears that the early church not only understood the that the baptism in the Holy Spirit was subsequent to salvation, but also recognized the importance of having every believer receive this experience.

3. 2. Initial Evidence

The initial evidence of the baptism in the Holy Spirit is speaking in tongues. Recalling Joel’s prophecy that the outpouring of the Holy Spirit will result in people engaging in prophetic utterances, when the disciples were filled with the Spirit on the day of Pentecost, Luke notes that they all spoke in tongues (Acts 2:4).[13] This pattern continues when the Holy Spirit fell upon Cornelius and his household and they were heard “speaking in tongues and extolling God” (Acts 10:46). On another occasion, when Paul laid his hands on the Ephesian believers, Luke reports that the Holy Spirit came upon them and they “spoke in tongues and prophesied” (Acts 19:7). Although other episodes of Spirit-baptism in the Acts narratives do not explicitly give evidence of tongues speech, John Wyckoff contends that it would have been obvious to Luke’s readers that believers spoke in tongues when they were Spirit-baptized so he did not always feel obligated to point it out.[14] While many scholars acknowledge that tongues often follow this experience, some do not agree that tongues are the initial evidence for all Spirit-filled believers. Clark Pinnock contends that tongues should be seen as a noble and edifying gift but not normative for everyone who is baptized in the Holy Spirit.[15] Despite some differing viewpoints, there is substantial and convincing evidence that tongues is the initial evidence of the baptism in the Holy Spirit within the Acts narratives and should be expected in all believers.

3.3. Availability

The baptism in the Holy Spirit was understood to be an experience for all believers and continues to be available today. Following the Pentecostal outpouring, Peter addresses his fellow Israelites and exhorts them to repent, be baptized in the name of Jesus, and receive the “gift” of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:38). Recalling the words of Jesus who referred to giving of the Holy Spirit as a “gift” (Lk. 11:13), Peter emphasizes the universal availability of Spirit baptism and the expectation that the charismatic experience would continue to be received by believers beyond the current age. “For the promise is for you, for your children,” Peter states, “and for all who are far way, everyone whom the Lord our God calls to him” (Acts 2:39). Affirming Joel’s prophecy, which understood the outpouring of the Holy Spirit to be continually being fulfilled throughout the last days, Peter publicly declared that the baptism in the Holy Spirit was not intended merely for the upper room gathering, nor was it a one time event, but was designed to be experienced for all believers.[16] Although some scholars maintain their opinion that the charismatic experience ceased after the apostolic age and is no longer available, countless millions of Christians continue to receive the baptism in the Holy Spirit around the world, demonstrating that the Pentecostal experience did not expire at the end of the apostolic age, but remains an empowering and life-transforming experience in the contemporary context.

3.4. Purposes

Although the purposes of the baptism in the Holy Spirit are as vast and diverse as the dynamic nature of God’s Spirit, this section will highlight two significant ways the charismatic experience influences believers. First, the baptism in the Holy Spirit empowers believers for gospel proclamation in the world. Prior to the day of Pentecost, Christ informed the disciples that they will be filled with δύναμις, meaning force, miraculous power (usually by implication a miracle itself) to “be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).{C}[17]{C} Through this anointing of spiritual power, Christ enabled the disciples to fearlessly proclaim the gospel of salvation to a lost and broken world. To illustrate, when Ananias was instructed by the Lord to pray for Paul to receive the baptism in the Holy Spirit, the Lord clearly articulated the purpose for his infilling: “he is an instrument whom I have chosen to bring my name before Gentiles and kings and before the people of Israel” (Acts 9:15). Clearly apparent from the text, although Paul was converted, he was not sufficiently prepared to commence his missionary activities without first being empowered by the Holy Spirit. This is not to say that believers who have not received the baptism in the Holy Spirit would be ineffective in their witness, but just as the Holy Spirit empowered Jesus for his mission, so the Holy Spirit empowers believers for their mission to bear witness to the resurrected Christ.

Second, the baptism in the Holy Spirit equips believers to function in the gifts of the Spirit.[18] Although the Bible records many miraculous demonstrations of the supernatural in the lives of Old Testament individuals and in the lives of New Testament believers both before and after their baptism experience, there is definitely a higher incidence of spiritual gifts operating through Spirit-filled members of the early church than there was prior to the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.[19] More than just speaking in tongues, the baptism in the Holy Spirit is the gateway that leads to numerous supernatural manifestations of the Holy Spirit in the lives of believers.[20] Shortly after Pentecost, Luke highlights how the Spirit-anointed leaders of the early church began functioning in the gifts of the Holy Spirit, stating, “Awe came upon everyone, because many wonders and signs were being done by the apostles” (Acts 2:43). Not confined to the apostles, Luke also illustrates how other members of the early church community functioned in the supernatural gifts of the Holy Spirit. Stephen, who was “full of the Holy Spirit” went around doing “great wonders and signs among the people” (Acts 6:5, 8). Additionally, Philip, who was also Spirit-filled, preached the gospel to crowds of people, performed miraculous signs, exorcized demons, and healed the sick (Acts 8:6-7). For Luke, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecostal was a critical turning point for the disciples; they had entered into a new relationship with the Holy Spirit that enabled them to continue the mission of proclaiming Christ to the world through the power and gifts of the Holy Spirit.

4. Summary

Throughout the Scriptures, it is clear that the baptism in the Holy Spirit is an experience that empowered and equipped the early church for their mission to bear witness to the resurrected Christ. The Old Testament prophecies anticipate a dual role for the Holy Spirit: to indwell people for regeneration and to fill people for prophetic empowerment. Jesus’ pre-resurrection teachings describe the Holy Spirit as a gift given by the Father to everyone who asks and a counsellor for the disciples when they face persecution. Following his resurrection, Jesus describes the coming Holy Spirit as an immersive event that will empower the disciples for witnessing. Throughout the Acts narratives, the baptism in the Holy Spirit is an experience subsequent to and separate from conversion and is initially evidenced by speaking in tongues. Most importantly, Spirit-baptism is to be a normative experience for every Christian that empowers them to witness and equips them to function in the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

Part 2: Practically Applying Spirit-Baptism to the Emerging Church

Understanding that the baptism in the Holy Spirit is grounded in the teachings of Scripture, part two of this study will concentrate on the practical application of Spirit-baptism in the emerging church within an urban Canadian context. Divided into three parts, the first section will identify the nature and characteristics of the emerging church, the second part will outline a four step plan to implement the baptism in the Holy Spirit in the emerging church, and the final section will address some concerns that emerging church leaders may encounter when implementing Spirit-baptism into their ministry context.

5. Understanding the Emerging Church Context

Starting in the early 1990’s, the emerging church has become a significant movement within the Christian community that focuses on rediscovering the essential message of Christ and sharing it with the post-modern generation.{C}[21] According to Scot McKnight, there are five key elements that define the nature and characteristics of the emerging church.[22] First, the emerging church is prophetic. Consciously provocative, McKnight notes how the emerging church believes that the traditional church is no longer able to communicate the gospel to the contemporary post-modern culture. Rejecting traditional church methodologies, the emerging church endeavours to model authentic Christianity to their community according to a missional ecclesiology that embraces the life and mission of Jesus. Second, the emerging church is post-modern. Within this framework, the inherited meta-narratives that have previously explained the knowledge and experience of the modern culture have been replaced with local narratives that facilitate the interpretation of present reality.[23] Rejecting the propositional truths that have anchored the traditional church, the emerging church is on a “faith seeking understanding” expedition that desires to experience authentic spiritual formation without the religious construction of the previous generation.[24] Third, the emerging church is praxis-oriented. Rather than hearing about the gospel from a pulpit, the emerging church embraces a missional ecclesiology that actively participates in community transformation through the redemptive work of God in the world. Fourth, McKnight contends that the emerging church is post-evangelical. Unwilling to be lumped together with the dominant evangelical religious sub-culture and its specific theological, social, and political leanings, the emerging church prefers to be seen as an authentic community of Christ followers that accepts everyone regardless of socio-economic status, race, or sexual orientation.[25] Last, the emerging church is political. Positioning themselves more with the Liberals than the Conservatives, Jonathon Smith contends that the emerging church tends to be more ideologically aligned with the political parties that are committed to the poor and the marginalized.[26] Although they do not approve of abortion and gay marriage, they strongly support political initiatives that fight for social justice and equality within their communities.

6. Introducing Spirit-Baptism to the Emerging Church

Fuelling the emerging church movement is a missional ecclesiology that focuses on spiritual formation and community transformation within the post-modern context. Since the nature of the baptism in the Holy Spirit is oriented towards mission, embracing the experience can supernaturally empower and equip the emerging church to fulfil their missional endeavours. To introduce the baptism in the Holy Spirit to the emerging church, this section will implement a four step process modelled after the biblical pattern: teaching, experiencing, practicing, and sharing.

6.1. Teaching

Prior to the reception of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost, Jesus taught the disciples about the person and work of the Holy Spirit. Both his pre- and post-resurrection teachings informed the disciples about the nature and characteristics of the coming outpouring of the Holy Spirit. As missional leaders within the emerging church, teaching about the baptism in the Holy Spirit introduces people to the charismatic experience in a welcoming and informal conversational environment. Since one of the features of the emerging church is the rediscovery of ancient stories of spirituality, emerging leaders can engage their churches in a communal dialogue about the person and work of the Holy Spirit directly from the biblical text. According to futurist Leonard Sweet, the ancient ways are more relevant than ever. Writing in Post-Modern Pilgrims, he states:

The mystery of how ancient words can have spiritual significance in this new world is evident in the cultural quest for ‘soul’ and ‘spirit.’ The very talk of soul and spirit is the talk of a very ancient language, a first century language largely abandoned by the modern world but a language more fitting today than ever.{C}[27]

With an emphasis on the Old Testament prophecies, the words of Christ, and the Acts narratives, emerging leaders can facilitate conversations about the ancient workings of the Holy Spirit and the relevancy of Spirit-baptism to the contemporary context. Through sensitive dialogue and open discussion, those truly desiring to model authentic Christianity may begin to express an interest in venturing to the next phase in the discipleship journey: the experience of being baptized in the Holy Spirit.

6.2. Experiencing

Following Jesus’ pre- and post- resurrection teaching, the next step for the disciples in their journey of faith was the actual experience of Spirit-baptism. Taking place during a worship event in an upper room in Jerusalem, Luke describes the event in dramatic detail:

When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability (Acts 2:1-4).

Since the desire to experience authentic spiritual formation is a common maxim among emerging church participants, learning about the baptism in the Holy Spirit will inevitably lead some to start seeking the baptism in the Holy Spirit. To facilitate their reception of the experience, emerging church leaders can provide a variety of spiritually-sensitive worship settings where seekers can gather for times of authentic praise and prayer in anticipation of the supernatural gift.[28] When the Holy Spirit is poured out in these worship environments, often those who receive the baptism in the Holy Spirit have an intense spiritual experience and are overcome with emotion. Speaking in tongues for the first time, they are suddenly able to commune with Christ in a way not previously experienced. For Byron Klaus, the ability to speak in tongues enables believers to experience an entirely new level of spirituality. He writes:

Speaking in tongues is a vital part of the worship encounter, relating us directly to God. It transcends the ordinary limitations of speech and enters a level of encounter with God that goes beyond mere lip service. It allows a person to act in accordance with new and previously unimagined possibilities not drawn out of already existing perceptions of reality.[29]

Affirmed through Joel’s prophecy, this new level of spirituality through the baptism in the Holy Spirit opens the door to prophetic utterance speech, dreams, visions, and other supernatural manifestations that edify both the individual and the church. Through this life-changing experience, the Holy Spirit becomes a central part in the development of authentic spiritual formation and the primary motivator for participation in the kingdom of God.

6.3. Practicing

The next step in the disciples’ journey of faith was to put their experience into practice. Following the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost, Luke reports that the disciples immediately began fearlessly proclaiming the gospel to the gathered crowds (Acts 2:14) and demonstrating the power of the Holy Spirit through signs and wonders (Acts 2:43). The disciples were aware that their experience was not simply for their own benefit, but was designed to fuel their mission to spread the good news of Christ to all people. Since the emerging church is praxis-oriented and already actively participating in the redemptive work of God in the world, integrating their experience of Spirit-baptism with a missional ecclesiology will take ministry to an entirely new level of effectiveness. According to Lim:

The baptism in the Holy Spirit is not primarily a qualifying experience but an equipping experience. It enables Christians to do the job more effectively. The person who is fully yielded to the Holy Spirit will find a greater dimension of ministry than could be realized without the infilling.[30]

Through a variety of creative ministry initiatives, Spirit-filled emerging churches can incorporate practical, hands-on community service projects through the anointing of the Holy Spirit. When helping the poor and marginalized, not only can Spirit-baptized believers support their physical and social needs, but also minister to their spiritual needs as well. When standing up for social justice issues in the political sphere, having the discernment, wisdom, and boldness of the Holy Spirit is critical to being heard among competing voices. When praying for the moral deficits of the inner-city, developing intercessory prayer groups that engage in spiritual warfare through the power of the Holy Spirit can create unimaginable possibilities for healing and reconciliation. When emerging church participants put their experience into practice, ministry effectiveness increases, lives are transformed, and the redemptive work of Christ is extended throughout the urban community.

6.4. Sharing

The fourth step in the journey of faith for the disciples was the ongoing ministry of sharing the experience of Spirit-baptism with others. According to Luke’s account, after the disciples received the baptism in the Holy Spirit and started putting their experience into practice, they also began to pray for others to receive the experience. To illustrate, after Ananias was filled with the Holy Spirit, he prayed for Paul to receive the Holy Spirit (Acts 9:17); in turn, Paul laid his hands on the Ephesian men and “the Holy Spirit came upon them, and they spoke in tongues and prophesied” (Acts 19:2-7). Recognizing the immense value of Spirit-baptism to the overall mission of the church to witness to the resurrected Christ, the disciples earnestly passed on the gift of the Holy Spirit to others. When the emerging church imparts the gift of the Holy Spirit to others, more people are empowered and equipped to participate in the redemptive reign of Christ in the world. Keeping the experience insulated is not an option; the very design of baptism in the Holy Spirit is outward and focused on the kingdom of God. In his book, Pentecostal Spirituality, Steven Land writes, “The passion for the kingdom is the ruling affection of Pentecostal spirituality and not the mere love of experience for experience’s sake.”[31] Just as the disciples shared the experience with others, when the emerging church explains the baptism in the Holy Spirit to fellow believers and prays for them to receive the gift, they are fulfilling the mandate of their missional ecclesiology to be an authentic, life-giving, and Spirit-led community of Christ followers in the post-modern context.

Part 3: Addressing Post-Modern Suspicions about Spirit-Baptism

Although the baptism in the Holy Spirit is supported in the biblical accounts of the early church and is expected to be a normative experience for all believers, practically applying Spirit-baptism in the emerging church may provoke some negatives responses. According to Eddie Gibbs, the overarching meta-narratives existing in the biblical text are often obstacles to the reception of biblical teaching among post-moderns. He states, “Big stories [grand meta-narratives] that provide an explanation of life and that demand the total allegiance of ‘true believers’ are assumed to be controlling devices or power grabs.”[32] Moreover, Gibbs asserts that when biblical teaching is framed in propositional statements and presented as absolute truth for all people, post-moderns become suspicious and often end up rejecting the church’s message. To avoid presenting doctrine as an overarching meta-narrative or a propositional truth, Gibbs offers a more promising approach that focuses on the “little” story. To apply his approach to the practical application of Spirit-baptism in the emerging church, it would be beneficial for believers who have already experienced the baptism in the Holy Spirit to share their personal story with others. By integrating the “little” stories of how God spiritually empowers and equips people for ministry with the ancient accounts of the early church through the Acts narratives, the message of Spirit-baptism is communicated in a non-confrontational manner. Although there will always be some dissenting or disapproving voices, sharing the message of the baptism in the Holy Spirit through story helps to minimize some of the doubts in the post-modern generation.

Conclusion

Grounded in the teachings of Scripture, the baptism in the Holy Spirit is an experience that empowers and equips believers to be witnesses of the resurrected Christ. Anticipated by the prophet Joel, taught by Jesus, and experienced by the followers of Christ throughout the Acts narratives, the baptism in the Holy Spirit was an essential part of the missional ecclesiology of the early church. Practically applying the experience of Spirit-baptism to the emerging church can increase ministry effectiveness, transform lives, and extend the redemptive work of Christ in the world. Modelled after the biblical pattern, emerging leaders can introduce the experience of Spirit-baptism by teaching on the nature and characteristics of the Holy Spirit from the biblical text. For those desiring to experience the baptism in the Holy Spirit, emerging leaders can facilitate the reception of the experience by providing worship settings where people can gather for times of authentic praise and prayer. When people receive the baptism in the Holy Spirit, they can put their experience into practice through a variety of missional initiatives that witness to the resurrected Christ. As they minister, they can also share their experience by telling their story and praying for others to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. Although there are challenges to presenting the concept of Spirit-baptism to post-moderns, avoiding overarching meta-narratives and emphasizing personal stories can minimize some of the doubts inherent in post-modern thinking. For the emerging church, the desire to personally experience authentic spiritual formation and participate in community transformation makes the experience of Spirit-baptism an essential component in their overall missional ecclesiology. By embracing the ancient charismatic experience, the emerging church can be empowered and equipped to be effective witnesses of the resurrected Christ to the emerging post-modern generation.

Bibliography: Anderson, Allan. An Introduction to Pentecostalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Gibbs, Eddie. LeadershipNext: Changing Leaders in a Changing Culture. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2005. Hammett, John S., “An Ecclesiological Assessment of the Emerging Church,” Criswell Theological Review 3:2 (2006): 29-49. Horton, Stanley M. Systematic Theology. Springfield: Logion Press, 2007. Horton, Stanley M. What The Bible Says About The Holy Spirit. Springfield: Gospel Publishing House, 1976. Land, Steven J. Pentecostal Spirituality: A Passion for the Kingdom. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993. Lim, David. Spiritual Gifts: A Fresh Look. Springfield: Logion Press, 1991. McKnight, Scot, “Five Streams of the Emerging Church,” Christianity Today 51:2 (2007): 34-39. Palma, Anthony D. The Holy Spirit: A Pentecostal Perspective. Springfield: Gospel Publishing House, 2001. Russinger, Greg and Alex Field, eds. Practitioners: Voices Within the Emerging Church. Ventura, CA: Regal Books, 2005. “The Baptism in the Holy Spirit: The Initial Experience and Continuing Evidences of the Spirit-filled Life,” Position Paper of the General Council of the Assemblies of God (USA), http:www.ag.org/top/beliefs/position_papers/pp_4185_spirit-filled_life.cfm, (accessed March 3, 2008). Sampson, Philip, Vinay Samuel & Chris Sugden, eds. Faith and Modernity. Oxford: Regnum Books, 1984. Smith, Jonathon. “The Emerging Church.” Lecture, Agincourt Pentecostal Church, Scarborough, ON, March 7, 2008. Strong, James. Strong’s Hebrew and Greek Dictionaries. QuickVerse for Windows on CD-ROM. Version 2007, 2003. Stronstrad, Roger. The Prophethood of All Believers. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999. Stronstad, Roger. Spirit, Scripture & Theology: A Pentecostal Perspective. Baguio City, Philippines: Asia Pacific Theological Seminary Press, 1995. Sweet, Leonard. Post-Modern Pilgrims. Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2000.

Pentecostals as Innovator-Prophets of Contextual Ministry by William Sloos

As an explorer of Pentecostal history, I took the opportunity to visit the Angelus Temple while on vacation in Los Angeles earlier this year. For those unaware of its significance to our early Pentecostal story, the Angelus Temple is a monument to the visionary leadership of its founder, Canadian Pentecostal evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944). When the Angelus Temple opened in 1923, it was an awe-inspiring structure bearing a massive unsupported dome, an expansive sanctuary, and two stately balconies with a total seating capacity for 5,300 people. Sister Aimee, as her followers affectionately called her, held 16 services every week – some services overflowing with up to 7,500 people. Within the first six months, some 8,000 people professed conversion, and 1,500 people were baptized in water. Thousands of seekers were attracted to the Angelus Temple to witness Sister Aimee communicate “Biblical Christianity” in contemporary language, symbols, imagery, and imagination. Renowned for her immensely popular illustrated sermons, one Sunday Aimee appeared on the Temple platform wearing a police uniform, standing beside a motorcycle with sirens blaring, warning her hearers that they were speeding down the wrong avenues of life. Employing innovative approaches and leading-edge media, Aimee embraced many of the emerging technological developments of the early twenties to communicate the gospel to the emerging Los Angeles culture. As an innovator-prophet of contextual ministry, Sister Aimee was a leading example of how early Pentecostals were adept in communicating the gospel in contemporary ways through the power of the Holy Spirit.

Almost a century later, the Angeles Temple continues to thrive as a centre of missional Pentecostal ministry on the West Coast. Following in Aimee’s footsteps of innovative and prophetic contextual ministry, visionary-leader Matthew Barnett and his team are proclaiming Christ through the unapologetic adaptation of cutting-edge methodologies. Without assuaging the message or quenching the Spirit’s power, today’s Angelus Temple reverberates with energy, creativity, and multi-media innovations that all contribute to the highly contextual presentation of the gospel. When my wife and I arrived for the second Sunday morning service, crowds of people packed the foyer making it difficult to navigate as first-time visitors. Although early for the service, we squeezed into our balcony seats with a palpable sense of the deep-seated hunger for God among those gathered at the front for pre-service prayer. I immediately noticed that I was among the few “older people” in attendance – I’m 38 years old. Brimming with the vibrancy of thousands of youth and young adults, the service opened with high energy, high quality, and high intensity praise including rock, rap, and rhythm and blues with guitar riffs that would have delighted Larry Norman. With all the spot lights, big screens, and dry ice, I wondered if the audience would be comprised of entertained spectators rather than exalting worshippers. Not so. People surrounding me lifted their arms, opened their hands, and raised their voices in worship; some with tears, others with shouts of praise. This was not a seeker-sensitive service- this was a seeker-immersive service. There were no lattes or cappuccinos, mid-service coffee breaks, or friendly welcome teams to ease our first-time experience. Rather, we were immersed into a highly contextual shared worship experience centred on exalting Christ and proclaiming salvation to a hurting and broken community.

As the service progressed, the charismatic yet somewhat quirky Matthew Barnett led in prayer and then introduced us to “Samantha” from “Saskatchewan, Canada.” Samantha, a twenty-something First Nations woman wearing a black T-shirt and jeans stood beside Pastor Matthew to share her testimony of life-transformation. Samantha explained how she came from an abusive background, fled to Los Angeles to become an actress only to fall on hard times and become addicted to drugs and involved in prostitution. Through her tears, she shared about how a friend introduced her to the Angelus Temple ministry and how she found hope and redemption through a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. As the crowd erupted in cheers, Samantha exited the stage and the offering was collected while Maroon 5’s “Moves Like Jagger” boomed from the loud speakers. Mark Batterson, author of the book The Circle Maker,{C}[2] was the special guest speaker who shared passionately about a life dedicated to intercessory prayer and spiritual warfare. The service concluded with a salvation invitation and the opportunity to make your way to a side room where ministry teams were ready to pray for you. For those sticking around after the service, the LA Lakers v. Miami Heat basketball game would be playing on the big screens.

Following my experience at the Angelus Temple, it occurred to me that this service was not geared towards my middle class and middle age Canadian worldview. Matthew Barnett is deliberately and intentionally communicating Jesus to his local community. Echo Park, the urban neighbourhood where Angelus Temple is located, has one of the highest population densities in the nation and suffers high unemployment, low education, and low household income.[3] Using innovative words, symbols, imagery, and imagination familiar and meaningful to his community, Barnett is able to speak prophetically about Christ. Unhindered by the religious-historical baggage of past generations or the underlying holiness expectations within traditional evangelicalism, Barnett announces the kingdom in a way that connects to the heart and mind, soul and spirit of his community. An innovator-prophet of contextual ministry, Barnett has embraced the missional values and ethos inherent in the gospel that seeks to identify with real people in real situations in real time through the power of the Holy Spirit.

Having reflected on my visit to the Angelus Temple, I would like to share four things that may help us as Canadian Pentecostal leaders to become innovator-prophets in our own Spirit-filled contextual ministry.

1. Refuse the pressure to import historical Pentecostal methodologies simply because they are remembered as being successful in a previous generation. The phrase “Halcyon Days” is a term derived from Greek mythology that refers to an earlier time, remembered as idyllic, whether the memories are accurate or not. As the PAOC approaches a centenary of Spirit-filled Pentecostal ministry across Canada and around the world, some believers sit back and remember our own Halcyon Days – the glorious revival days of the past. However, as a researcher of Pentecostal history, I have discovered that our Halcyon Days do not actually exist. Every generation of Pentecostal ministry has its victories and vices, successes and setbacks, revivals and regrets, prophets of blessing and prophets of doom. When I hear a critical remark about how we are on a slippery slope or that the glory has departed, the same critical remarks were spoken in previous generations as well; ignore these critical remarks and press on.

2. Resist the temptation to adopt popular trends or fads within current evangelicalism that only produce cookie-cutter ministries with often only mediocre results in the local context. What the Holy Spirit conceived in Los Angeles is for Los Angeles. Our failure is when we catch a vision and then attempt to market it as the next great church growth model. We have proven to be masters of marketing, but have not effectively mentored our leaders to catch the wind of the Spirit for their own unique ministry context. We must allow the Holy Spirit freedom to breath life, vision, and creativity at the local level for the local community.

3. Repel the traditional holiness notion that we are to escape from culture to keep from being polluted by it. Although we are citizens of another world, we are ambassadors in this one. We must live redemptively in culture without either conforming to or separating from it. I grew up believing that secular music, sports on Sundays, and wearing shorts at church picnics was ungodly for a Spirit-filled Pentecostal; these notions have only served to fuel an obscure Pentecostal-holiness sub-culture and obstruct the loving, liberating, and life-changing proclamation of the gospel to a hurting and broken world. Let’s be real people living in the real world.

4. Revive our Pentecostal distinctive as innovator-prophets of Spirit-led contextual ministry by communicating the gospel through words, symbols, imagery, and imagination familiar to our local communities. As Aimee Semple McPherson and now Matthew Barnett innovatively and prophetically declare Christ to their generation, we too must actively penetrate the emerging generation with the life-transforming gospel. We are called to be innovators – pioneers of visionary-leadership to interest, inspire, and invite our local communities to a journey of faith. We are also called to be prophets – to announce the kingdom of God boldly and proclaim the liberty of Christ with persuasiveness, passion, and the power of the Holy Spirit. Although there will only ever be one Aimee Semple McPherson and Matthew Barnett, what is the Spirit saying to you and I about our own particular context? Are we willing to step out as innovator-prophets and lead a Spirit-filled contextual ministry of gospel transformation? Our friends, neighbours, and communities are watching and waiting.

Bibliography: Edith L. Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody’s Sister, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1993), pp. 232-280. See picture of Aimee’s illustrated sermons on p. 260. Mark Batterson, The Circle Maker: Praying Circles Around Your Biggest Dreams and Biggest Fears, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011). http://projects.latimes.com/mapping-la/neighborhoods/neighborhood/echo-park