History Papers

“We mistakenly think that memories are like carvings in stone; once done, they do not change. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Memory is not only selective, it is malleable.”

Tiled Ceiling Murals at the Wartburg Castle, Eisenach, Germany

Separated by the Scriptures: Erasmus' and Luther's Opposing Perspectives of the Bible by William Sloos

Luther and Erasmus' - The Final Fray

Considered one of the more memorable exchanges in western intellectual history, the theological dispute between Luther and Erasmus over the issue of justification in 1524-7 has largely been viewed as the defining feature of their enduring antagonistic relationship.[1] Although they shared the same conviction that the Church was rife with immorality and simony and had strayed from the fundamental teachings of Scripture, Erasmus and Luther were never unified in their pursuit of ecclesiastical reform.[2] At the core of their dispute was an irreconcilable difference in their perspective of the biblical text.[3] As a humanist, trained in the literary and rhetorical traditions of antiquity, Erasmus believed that recovering the great truths of Scripture would unify Christians and draw them into the perfect union of the body of Christ. [4] By applying the moral principles of the biblical text, people can align themselves with the philosophia Christi and be motivated to love God and their neighbours.[5] Rejecting scholastic hermeneutics which crafted theology through polarizing and discordant disputations, Erasmus contended that the essential message of the Bible was capable of bringing peace and harmony to humankind.[6] Luther, on the other hand, through his diverse education and his intense personal experiences, came to believe that the Scriptures created division. Discovering the message of the biblical text for himself separated him from the rest of the Church and forced him to stand alone before his accusers. For Luther, the Bible was not a message of unity, but of discord and disruption; to grasp the meaning of the Scriptures was to be converted from error and set on a collision course with the apostate Church.[9] Although some in the evangelical camp had hoped that Erasmus and Luther would join forces in the emerging movement to reform the Church, their polemical understanding of the nature and purpose of the biblical text quickly shattered any optimism for unity. The following study will argue that the inability for Luther and Erasmus to cooperate with each other largely stemmed from their opposing views of the Bible. For Erasmus, properly understanding the Scriptures unified people, for Luther, it separated.

Erasmus’ View of Scripture

To understand Erasmus’ views of Scripture, it is necessary to explore his humanist thinking. Generally regarded as the most important exponent of humanist philosophy in the Renaissance, Erasmus was first exposed to humanism under the influence of Alexander Hegius, a former pupil of Rudolph Agricola and director of the renowned humanist school at Deventer in The Netherlands.[11] Under Hegius, Erasmus was immersed in the literary and rhetorical traditions of Greek and Roman antiquity and the Early Church Fathers. With an enthusiasm for the classics and thorough training in Greek and Latin, Erasmus devoted himself to recapturing the works of the ancient authors that had been passed on to him by Petrarch and earlier humanist writers.[13] Dedicated to the cause of what he called the bonae literae or “good letters,” Erasmus was persuaded that restoring ancient literature availed the scholarly community to a greater quantity of human knowledge for the moral and spiritual enrichment of society.[14] Moreover, Erasmus was also an ordained priest and considered himself a “Christian” humanist.[15] Along with his aspiration to restore classical literature was an earnest desire to return to the simple faith expounded by Christ and expressed in the early Church.[16] Recognizing that the Roman Church had wandered away from the central teachings of Scripture, re-establishing the sacred texts alongside the ancient classics became the primary focus of his lifelong restorationist initiatives.[17]

Desiring to mesh his humanistic ideals with the biblical text, the Bible became central to Erasmus’ conception of bonae literae as a way to unify Christians and draw them into perfect union with the body of Christ.[18] In 1503, Erasmus wrote Enchiridion Militis Christiani (Handbook on the Christian Soldier), in which he developed the revolutionary and hugely popular thesis that the Church could be peacefully reformed by a collective return to the essential teachings of Scripture.[19] Having personally encountered the ignorant superstitions, empty religious rites, arbitrary moral codes, and flagrant ecclesiastical venality that dominated Christendom through the Roman world, Erasmus was convinced that common people needed to be able to read and understand the undistorted message of the Word of God for themselves.[20] Regarded as a lay person’s guide to the Scriptures, the Enchiridion provided a simple, yet learned exposition of the essential teachings of Jesus that informed Christians about good and evil so they could choose to live in harmony with the requirements of the divine law.[21] Later, when Erasmus published the monumental and much celebrated Novum Instrumentum omne (Greek New Testament) in 1516, he wrote in the prologue that his ultimate wish was for the farmer to chant the Bible at his plough, the weaver at his loom, the traveller on his journey, and even for women to read the text. The same year that Luther posted his ninety-five theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, driving a wedge between himself and the Church, Erasmus produced the Paraphrases, which were considered digests of the New Testament designed for popular consumption, making the Word of God available to the humblest and least educated. [23] Rather than having pretentious and misinformed theologians informing Christians on how to think and behave, Erasmus wanted the Scriptures internalized by everyone for the purpose of instilling a Christ-centred devotion that would flow from an inner contemplation of the essential truths of Scripture. Borrowing a phrase from Rudolf Agricola, Erasmus’ vision for society was to embrace the philosophia Christi, the learned wisdom of Christ to stimulate pious living and civil harmony in the humanist tradition. External rituals, creeds, and dogmas mattered little; such things brought division and discord. For Erasmus, arguments and disputations over non-essential doctrinal issues had inflicted enough chaos and conflict in the history of the Church. The Scriptures were not intended to divide people, but motivate them towards Christ-likeness and guide them in the way of unity and peace.

According to O’Malley, to encourage people toward pious living, Erasmus drew from a variety of classical and patristic sources to present his message.[25] First, Erasmus possessed a deep appreciation for the art of oratory that defined classical antiquity. To convince others to embrace the philosophia Christi of the Scriptures, there was no need for tedious inquiries, dogmatic assertions, or theological disputations, but through eloquent persuasion the great truths of Scripture could be effectively communicated to inspire people towards godly thinking and action. Second, Erasmus contended that all literature related to good and holy living had a didactic purpose. Along with the Scriptures, acquiring knowledge of all the great truths was critical for the promotion of human harmony and civility. From this perspective, Erasmus blurred the lines between the sacred and profane sources and absorbed the biblical text into the grand collection of classical literature. Third, Erasmus’ theological hermeneutics assumed that the Scriptures contained deeper levels of meaning other than the literal. Transmitted from the Augustinian methodology of biblical interpretation, Erasmus freely embraced allegory as a means of constructing meaning enabling him to concentrate on the broader concepts of the text, rather than argue about contradictory and irreconcilable theological matters. By adopting these humanistic principles to his perspective of the Scriptures, Erasmus was able to present a thoroughly congruous exposition of the Bible that he hoped would unite Christians to the cause of Christ while avoiding doctrinal controversies and maintaining ecclesiastical calm.

Luther’s View of Scripture

Standing at the Castle Church in Wittenburg, Germany. It was on these doors in 1517, Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses or Protests against the Roman Catholic Church, igniting the Protestant Reformation. The wooden doors have since been replaced by iron doors which permanently inscribe each of Luther's Theses.

Contrasting Erasmus’ view of Scripture as a way to unite Christians and draw them into fellowship with the philosophia Christi, Luther’s perspective of Scripture was one of division. Causing Luther to assume this segregative view of the biblical text was his diverse education and intense personal experiences. First, Luther’s education contained both scholastic and nominal philosophical thinking that contributed to his overall understanding of the Bible. According to O’Malley, Luther was exposed to the scholastic tradition early in his education and was accustomed to establishing clear distinctions, developing assertions, and engaging in dialectical reasoning.[26] Although Luther later fervidly rejected the via antiqua and its inadequate system of philological and logical analysis, Luther never purged himself of the need for doctrinal clarity. Whereas Erasmus could easily tolerate ambiguity in the biblical text, Luther was deeply uncomfortable with uncertainty and pursued firm theological positions. In addition, Oberman notes that when Luther entered the University in Erfurt in 1501, he was also introduced to nominalism which subordinated speculation to experience and taught him to freely question even the greatest thinkers of antiquity.{27] Years later, when Luther was summoned to defend his views of Scripture against the highly reputed scholastic authorities, his nominalist values enabled him to courageously question the long-standing doctrines and practices of the Church against the revealed Word of God. Combining an inherent scholastic disposition and nominal philosophical underpinnings, Luther’s vision of the Scriptures was greatly reoriented. He insisted on doctrinal clarity and did not shrink away from theological disputations to prove his biblical convictions; when challenged, he was able to boldly stand on the authority of God’s Word over and against the authority of the Church. In a letter addressed to the Emperor in 1521, Luther declared, “As I have offered myself thus I do now, excepting nothing save the Word of God, in which not only does man live, but which also the angels of God desire to see. As it is above all things it ought to be held free and unbound in all, as Paul teaches.”[28] For Luther, his diverse education equipped him to critically assess the significance of the Scriptures and render the biblical text “above all things,” a claim that ultimately and forcefully separated him from the Church.

Second, along with his education, Luther’s intense personal experiences also shaped his separative perspective of the Scriptures. According to Oberman, Luther became conscious of the polarizing nature of the Scriptures while studying at the university in Erfurt. At the time, the academic community was still in shock over the Church’s recent condemnation of Johannes of Wesel who was serving a lifelong prison sentence for insisting that Scripture alone was the final authority of faith.[29] Although Luther had not yet been called to the priesthood, this and other such stories circulating throughout the empire most likely contributed to his awareness of the power of the Scriptures to divide people.

When Luther entered the monastery in 1505, a pattern started emerging where Luther became increasing confronted with the divisive nature of the Scriptures. As a professor at the University of Wittenberg, his lectures on the Psalms prompted Luther to start viewing the Scriptures as having its own message, rather than a collection of various truths and proofs.[30] Although the notion that Scripture alone formed the foundation of theology was familiar among medieval scholars, recognizing it as something that was to be interpreted out of itself rather than through the heuristic devices of the Church was considered ground-breaking and carried with it certain risks. The risks of interpreting the message of the Scriptures on its own merit were described by Luther in a sermon in 1515 when he cautioned he listeners: “Whoever wants to read the Bible must make sure he is not wrong, for the Scriptures can easily be stretched and guided, but no one should guide them according to his emotions.”[31] Luther’s concern that the Scriptures could be wrongly interpreted indicated his awareness of the potential for the biblical text to cause division. Despite his own warnings however, his increasing insight into the central message of the Bible, apart from the doctrines and traditions of the Church, starting leading to debates over correct interpretations and meanings and eventually escalated into a direct challenge to the Church.

On October 31, 1517, the divisive nature of the Scriptures dramatically entered the public consciousness. After gathering together the main conclusions from his lectures on the Scriptures, Luther posted his ninety-five theses as a remonstration against the Tetzel scandal.[32] With the hope of sparking formal scholastic debate, Luther went to the extent of writing a protest letter to the Archbishop of Brandenburg declaring that “Christ has nowhere commanded Indulgences to be preached, but the Gospel.”[33] Persuaded that the immoral practices of the Church must cease and submit to the teachings of Scripture, Luther made his challenge a public matter and, with the help of the printing press, sparked a movement that was unable to be controlled by the existing hierarchies of the Church. According to O’Malley, through this experience, Luther became increasingly aware that the true teachings of the Word of God were being hindered because of the fixed policies of the Church.[34] While he affirmed that the true and invisible Church was the perfect body of Christ, Luther believed that the visible Roman Church had broken away from her Scriptural moorings and was morally and spiritually adrift. Moreover, the Church had been disconnected from the teachings of Scripture for so long that the existing leadership was no longer able to distinguish divine truth from ecclesiastical tradition. After suppressing the Word of God for centuries, when people exhorted the Church to return to the teachings of Scripture, they were quickly suppressed. Luther’s immense and fearsome discovery was that a return to the authority of biblical text was either going to bring his life to a sudden conclusion or was going to trigger a violent separation between the unbending ecclesiastical hierarchy and those who chose to follow the Scriptures as the only authority for faith and doctrine. Following his excommunication by Pope Leo X, Luther was summoned to the Diet of Worms to stand before Charles V in 1521. Requested to answer for his long list of books against the Papal Church, Luther’s courageous response highlights how the Scriptures had separated him from the Church. “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Holy Scriptures, which is my basis; my conscience is captive to the Word of God. Thus I cannot and will not recant, because acting against one’s conscience is neither safe nor sound. God help me. Amen.”[36] For Luther, the Bible was not a message of unity, but of separation and disruption; to grasp the meaning of the Scriptures was to be converted from error and set against the Church. From these dramatic personal experiences, Luther’s perspective of Scriptures was radically reoriented; not only did Scripture stand alone (sola scriptura), but Luther stood alone with it (sto unus).

Erasmus and Luther in Conflict

Leading up to their famous theological dispute over the issue of justification in 1524-7, Erasmus’ and Luther’s divergent perspectives of the biblical text are demonstrated throughout their correspondences. An early hint of their forthcoming rivalry over their opposing views of Scripture is seen in a letter from Luther to Spalatin in 1516. After Erasmus published his Novum Instrumentum omne, Luther was one of the first theologians to receive a copy and immediately began studying the Greek text for use in his Romans lectures. Frustrated by Erasmus’ failure to support a critical point of Pauline teaching, Luther complains to Spalatin:

What displeases me in Erasmus, though a learned man, is that in interpreting the apostle on the righteousness of works, or of the law, or our own righteousness, as the apostle calls it, he understands only those ceremonial and figurative observances. Moreover, he will not have the apostle speak of original sin, in Romans, chapter V, though he admits that there is such a thing.[38]

A precursor to their future conflict over justification, Luther identifies a subtle, but very significant oversight in Erasmus’ commentary of Romans 5: he minimizes the doctrine of original sin and the total inability for humankind to be justified according to their good works. Since Erasmus promulgated a practical morality of loving God and humankind through obedience to the philosophia Christi, emphasizing the doctrine of original sin would only serve to discourage people from embracing his pious ideals. For Luther, his Romans study informed him that humanity was utterly lost and incapable of justification through good works; regeneration could only be accomplished through faith in the righteousness of Christ. As he was coming to grips with this ontological reality, Luther was also viewing the Catholic system of penance and the burgeoning indulgence racket as a direct contradiction to the teaching of justification from the book of Romans. In light of the Church’s fervent promotion of good works, Erasmus’ failure to address an essential biblical doctrine was a watershed moment for Luther. His perspective of the Scriptures was separating him from Erasmus’s theologically weak and inadequate commentary and fuelling his growing animosity towards the Church. Although Luther was still a year away from publicly challenging Rome on the issue of indulgences, the Scriptures were already creating division between Luther and Erasmus as well as Luther and the Church.

Shortly after Luther posted the ninety-five theses and opened the floodgates of theological controversy, Erasmus’ and Luther’s divergent perspectives on the Scriptures were becoming widely known throughout the empire. Worried that his vision of unifying Christians through the philosophia Christi was being threatened, Erasmus wrote to Luther in the spring of 1519, extolling the virtues of peace and counselling him against creating further division. “I try to keep neutral,” Erasmus told Luther, “so as to help the revival of learning as much as I can. And it seems to me that more is accomplished by this civil modesty then by impetuosity.” A few months later, Erasmus wrote the archbishop of Mainz to discuss the increasingly unsettled events surrounding Luther’s divisive behaviour. He informed the archbishop: “I urged him [Luther] in passing to publish no sedition, nothing derogatory to the Roman pontiff, nothing arrogant or vindictive, but to preach the gospel teaching in sincerity with all mildness.” Despite Erasmus’ abhorrence for some of the doctrines and practices of the Church, he believed there was no reason to stir up the people and cause division. Peaceful reformation could be accomplished when Christians start reading and applying the essential truths of Scripture and aligning themselves with the teaching of Christ. Luther however, was suspicious of Erasmus’ passivity and believed that he was more dedicated to humanism than the Word of God. Although he acknowledged Erasmus’ well-intentioned efforts for peace, Luther was convinced that calling for peace would merely sustain the suppression and prohibition of the Scriptures.[42] Refusing Erasmus’ counsel, Luther proceeded to oppose the shameful behaviours of the Church with the Word of God. From this point forward, Erasmus’ vision of the Scriptures as a way of unifying Christians was swallowed up by Luther’s expanding mission to install the Word of God as the singular authority for doctrine in the Church. For Luther, there would be no middle ground, no compromise, and no unity until the Church submitted to the Word of God.

Following his return from the Wartburg castle in 1522, Luther resumed his lectures on the Scriptures at the University of Wittenberg. Continuing to wield the sword of the Spirit to separate truth from falsehood, Luther wrote his colleague Œcolampadius to articulate his opinion of Erasmus’ biblical hermeneutics:

I greatly wish he [Erasmus] would stop commenting on the Holy Scriptures and writing his Paraphrases, for he is not equal to this task; he takes up the time of his readers to no purpose, and delays them in their study of the Scriptures…you ought rather to be glad if what you think about the Scriptures displeases him, for he is a man who neither can nor will have a right judgement about them, as almost all the world is now beginning to perceive.[43]

Vividly conscious of the difference between Erasmus’ view of the text and his own, Luther encouraged his colleague not to concern himself with the humanist’s theological leanings. Luther even suggests to Œcolampadius that contrasting Erasmus’ perspective of the Scriptures would be beneficial in gaining a correct understanding of biblical truth. Through Erasmus’ blurring of sacred and profane literature and his persistent emphasis on the ambiguity of the text, Luther contended that Erasmus is only preventing his readers from accessing the truth and is perpetuating the blind ignorance that had suffused the Church for centuries. For Luther, the message of the Scriptures was not to promote universal peace and harmony through the assimilation of a broad selection of Christological precepts, but rather to reveal the guilty state of humankind and the provision of grace through the atonement of Christ.[44] Rather than uniting humankind through practical morality, Luther views the Word of God as a dividing force, separating truth from falsehood, believers from non-believers, and authentic faith from the counterfeit religion.

Leading up to their now famous theological dispute, Erasmus’ growing dislike for Luther’s immoderate writings made it impossible for him to remain silent. Persuaded by Pope Leo X and the Roman curia to take up the pen against Luther, Erasmus chose the contentious issue of justification to attack Luther’s evangelical doctrines.[45] Following Erasmus’ sober and scholarly publication of De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio (Diatribe or Comparison on Free Will) in 1524, Luther counter-attacked a year later with his own more petulant treatise, De servo arbitrio (On the Bondage of the Will).[46]

Wartburg Castle (1067). Under the threat of execution, Luther went into hiding at the Wartburg Castle under the alias Junker Jorg and there translated the New Testament from Greek into German to the make the Scriptures accessible for the whole German nation.

Within their polemical debate, Erasmus’ and Luther’s irreconcilable differences in their perspectives of the biblical text quickly rose to the surface. Believing that the essential teachings of Scripture could unify Christians, Erasmus explained that it is not always wise to make theological assertions from the Scriptures; since the meaning of biblical text is often ambiguous, it would be better to withhold asserting doctrinal truth for the sake of Christian unity.[47] He states, “So far am I from delighting in ‘assertions’ that I would readily take refuge in the opinion of the Skeptics, wherever this is allowed by the inviolable authority of the Holy Scriptures and by the decrees of the Church.”[48] As a humanist, trained in the literary and rhetorical traditions of antiquity, Erasmus had little confidence in the intrinsic value of doctrine. Considering that the biblical text was largely unclear, making doctrinal assertions was superfluous and frequently created contention and division among Christians. Rather than concentrating on making doctrinal claims, Erasmus desired to focus on the moral precepts that lead to piety. For Erasmus, Christ came to teach humankind the way of love and by reading and applying the essentials of the gospel, Christians can be motivated to love God and their neighbours. Responding to Erasmus’ position, Luther writes:

To take no pleasure in assertions is not the mark of a Christian heart; indeed, one must delight in assertions to be a Christian at all. Now, lest we be misled by words, let me say here that by ‘assertion’ I mean staunchly holding your ground, stating your position, confessing it, defending it and persevering in it unvanquished…And I am talking about the assertion of what has been delivered to us from above in the Sacred Scriptures.[49]

Since Luther’s initial correspondence with Spalatin over Erasmus’ failure to assert the basic Christian doctrine of original sin a decade earlier, Luther had personally faced several confrontations over his belief in the supremacy of the Scriptures. Following the posting of his ninety-five theses in 1517, Luther defended the authority of the Scriptures at the Heidelberg disputation, faced questioning by Cardinal Cajetan, debated Eck in Leipzig, and refused to recant before the Emperor at the Diet of Worms. For Luther, standing up for the Scriptures became a defining feature of his evangelical faith. Unlike Erasmus, who viewed the Scriptures as too ambiguous for doctrinal assertions, Luther continued to stand his ground over the obvious claims in the biblical text, regardless of the conflicts that it created. For Luther, the Scriptures did not bring unity, they brought division. Despite of the consequences however, he was persuaded that the Word of God must continue to be proclaimed without compromise; if it separates people, so be it.

Conclusion

Although Erasmus and Luther shared the conviction that the Church had strayed from the fundamental teachings of Scripture, they were never able to join forces in the emerging movement to reform the Church. At the centre of their dispute was an irreconcilable difference in their perspective of the biblical text. Erasmus, a humanist trained in the literary and rhetorical traditions of antiquity, believed that recovering the essential truths of Scripture could unify Christians and draw them into perfect fellowship with the body of Christ. Luther, on the other hand, through his diverse education and his intense personal experiences, came to believe that the Scriptures created division. Unlike Erasmus, discovering the message of the biblical text separated Luther from the rest of the Church and forced him to stand alone before his enemies. For him, the Scriptures did not inspire unity, but rather divided truth from falsehood, orthodoxy from heresy, and the disciples of Christ from the enemies of the cross. Erasmus’ and Luther’s divergent perspectives on the nature and purpose of the Scriptures were evident throughout their antagonist relationship but reached a climax when they clashed over the issue of justification. Considering the biblical text ambiguous, Erasmus refused to make doctrinal assertions for fear they might divide people and upset the stability of the Church. Opposing this view, Luther claimed that the Scriptures were clear and the apostate Church must be confronted with the truth regardless of the consequences. Despite the optimism of some in the evangelical camp who hoped that Erasmus and Luther would work together in the effort to reform the Church, their opposing views of the biblical text prevented any possible cooperation. For Erasmus, the Scriptures were intended to unify people; for Luther, the Scriptures separated people and set them against the abusive and corrupt Roman Church.

Bibliography: Cross, F. L. and E. A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. Cummings, Brian. The Literary Culture of the Reformation. Oxford: Oxford University] Press, 2002. Dillenberger, John, ed. Martin Luther: Selections from His Writings. New York: Doubleday, 1962. Levi, Anthony. Renaissance and Reformation: The Intellectual Genius. London: Yale University Press, 2002. MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation: A History. New York: Penguin Group, 2003. Martin Luther’s Letters, “To Lord Albrecht, Archbishop of Magdeburg and Mayence, Mark-grave of Brandenburg From Martin Luther, October 31, 1517,” God Rules.Net. http://www.godrules.net/library/luther/208luther2.htm (accessed Friday, April 18, 2008). McGrath, Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction. Fourth Edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Oberman, Heiko A. Luther: Man Between God and the Devil. London: Yale University Press, 1989. O’Malley, John, W. “Erasmus and Luther, Continuity and Discontinuity As Key to Their Conflict,” Sixteenth Century Journal 5:2 (1974): 47-65. Preus, Daniel, “Luther and Erasmus: Scholastic Humanism and the Reformation,” Concordia Theological Quarterly 46:2-3 (1982): 219-230. Rummel, Erika. The Erasmus Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990. Rummel, Erika. Erasmus. London: Continuum, 2004. Smith, Preserved, ed. Luther’s Correspondence and other Contemporary Letters, Vol. 1. Philadelphia: The Lutheran Publication Society, 1913. Smith, Preserved and Charles M. Jacobs, eds. Luther’s Correspondence and other Contemporary Letters. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: The Lutheran Publication Society, 1918.

Healing in the Atonement: The Healing Ministry of John Alexander Dowie by William Sloos

John Alexander Dowie (1847-1907) Leader of the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church, Zion City, Illinois

Within the theologically informed and spiritually charged atmosphere of the second half of the nineteenth century, John Alexander Dowie emerged as one of the more colourful healing evangelists on the American religious landscape. At the zenith of his popularity, Dowie claimed over 250,000 followers world-wide with hundreds of people claiming healings at his meetings. Emphasizing the authority of Scripture and a personal faith in Jesus, Dowie taught that healing is sourced in the atonement of Christ and is assured for all repentant believers.[2] His soteriological perspective of healing began to appear when, as a young pastor in his native Australia, a dying woman was instantly healed in response to his prayers.[3] Resulting from this experience, Dowie made healing through the atoning work of Christ a central feature of his evangelistic ministry. Through his widely circulated weekly periodical, Leaves of Healing, Dowie declared that all sickness and disease originates in the demonic, but due to Christ’s defeat of Satan through his atoning sacrifice, healing is available to every person on the condition that they repent of their sins and exercise their faith.[4] Critical to preventing further afflictions and maintaining physical health was the avoidance of demonic influences such as medical treatment and pork products.[5] Despite Dowie’s extreme theology and increasing eccentricity later in life, his healing ministry experienced tremendous success and influenced many lives. This paper will demonstrate how Dowie’s healing ministry was soteriologically oriented and grounded in the atonement of Christ. Divided into two parts, the first part of the paper will be an overview of Dowie’s life and ministry and the second part of the paper will explore his theology of healing.

Dowie’s Life and Ministry

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1847, John Alexander Dowie immigrated to Australia as an adolescent.[6] Sensing the call of God on his life, he returned to Scotland to study theology at the University of Edinburgh and then returned to Australia to commence his pastoral ministry with the Congregational church.[7] After a succession of pastorates, he quickly climbed the ecclesiastical ladder and eventually garnered a prestigious position as pastor of the Collegiate Church in Newton, a suburb of Sydney. While serving in the Newton parish, Dowie’s life was dramatically changed when he witnessed a miraculous healing in response to his prayers. This experience convinced Dowie that divine healing is not just provided, but is assured in the atonement of Christ, a conviction that would radically transform his theology and ignite a healing ministry that would gain international attention.[9]

According to Dowie’s own testimony in Leaves of Healing, his life-changing experience occurred when a devastating plague was sweeping over eastern Australia in 1875.[10] Within a few weeks, Dowie had officiated at over forty funerals, including many from his own congregation. Exhausted and wrestling with thoughts of how a loving God could allow such immense suffering to persist, Dowie was called to pray for a young lady of his parish who was near death. Entering the room where the ailing woman lay, Dowie met her doctor and discussed the seriousness of the woman’s condition. Resigned to her inevitable fate, the doctor said to Dowie, “Sir, are not God’s ways mysterious?”[11] Indignant at the doctor’s insinuation that the woman’s disease was given according to divine providence, Dowie became angry. “That is the devil’s work,” Dowie declared, “and it is time we called on Him Who came to destroy the work of the devil.”[12] Persuaded from his reading of Scripture that the benefits of the cross also include healing, Dowie laid his hands on the woman and boldly interceded for her recovery in the name of Jesus.[13] Opening her eyes, the woman reported feeling better; the fever had disappeared and she was completely healed. Through this experience, Dowie became convinced that Jesus is both Saviour and Healer through his atoning work on Calvary.

Following several very successful years pastoring his own church in Melbourne, Australia, Dowie received a vision from God calling him to carry his message of divine healing to every nation. Fused with soteriological language, Dowie recalled his vision: “I…had to carry the Cross of Christ from land to land, and bid a sin-stricken and disease-smitten world to see that the Christ Who died on Calvary had made atonement for sickness as well as for sin, and that with his stripes we are healed.”14] Eager to proclaim the healing power of Christ through the atonement, Dowie left Australia for San Francisco in 1888 and began holding healing crusades along the Pacific coast. Eager for greater exposure, Dowie travelled to Chicago to coincide with the 1893 World Exposition and opened a healing booth on the fair grounds where he exhorted thousands of spectators to repent, put their faith in Christ, and receive their healing.[16]

Settling in Chicago, Dowie organized his followers into the Christian Catholic Church, opened healing homes, started his publication, and began conducting services in the spacious Zion Tabernacle.[17] With his ministry increasing in numerical and financial strength, Dowie began attracting the attention of the local authorities. Concerned with the activities occurring in his healing homes, Dowie was charged with practicing medicine without a licence.[18] Although he was never convicted, these charges garnered national attention for Dowie, who took the unsolicited publicity to rail against what he called the “Hosts of Hell in Chicago,” including the apostate clergy, lying press, “medical butchers,” dispensers of “distilled damnation,” and anyone else that opposed his message.[19] Despite alienating many in the community, thousands of people from across the social spectrum flocked to Dowie’s meetings in the hope of experiencing healing in their bodies. Confident in the healing power of Christ, Dowie laid his hands on the sick and prayed for their recovery resulting in hundreds of testimonies of people claiming to be healed.[20]

Dowie’s expanding ministry was soon paralleled by his increasing apotheosis. On New Year’s Eve 1899, Dowie unveiled plans for the development of a utopian community that would function as a theocracy in which he would be the sole interpreter of God’s laws. The community, known as Zion City, located north of Chicago, eventually grew to over 8,000 inhabitants with plans to expand to 200,000.[22] During this time, Dowie became increasingly more eccentric. He consecrated himself as “Elijah the Restorer” and “the first apostle of the renewed end-times church.”[23] As Dowie prepared to establish other Zion cities around the world, he suffered a mild stroke which caused his hold on the vast ministry to unravel.[24] With his health failing, he faced mounting evidence of financial mismanagement, charges of marital infidelity, and rumours that he was suffering from mental delusions.{[25] Disgraced, Dowie died in 1907, largely ignored by the thousands who were once devoted to him.[26] Had he lived, there was speculation that he would have eventually claimed to be the reincarnation of the Messiah.[27]

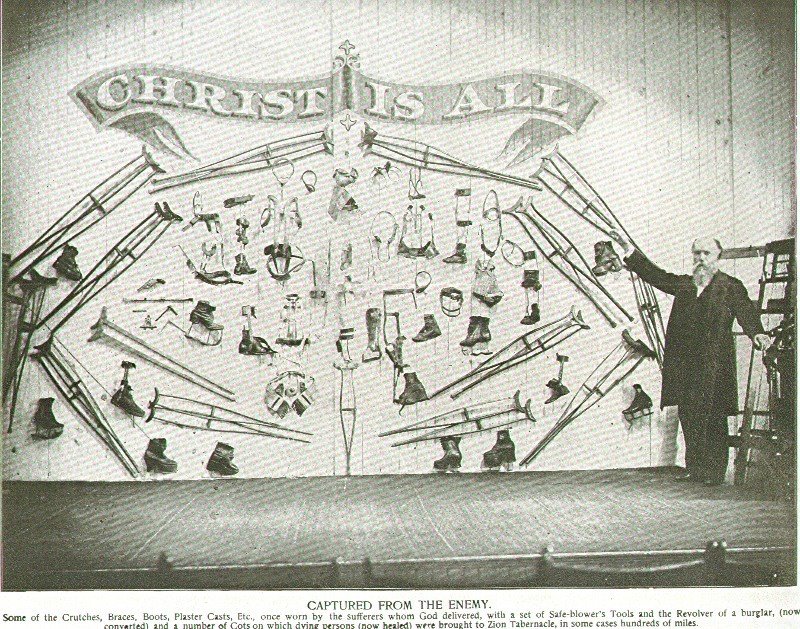

Medical and therapeutic devices left behind after healing services at Shiloh Tabernacle, Zion City, Illinois.

Dowie’s Theology of Healing

First, sharing similar theological perspectives with other faith healers of his era, Dowie claimed that divine healing is assured in the atonement.[28] He stated, “We teach that the Atoning Sacrifice of our Lord Jesus Christ covers all kinds of sin and its consequences, of which disease is one.”[29] Emphasizing biblical texts that support his doctrine, especially Isaiah 53:5 which states, “with his stripes we are healed,” Dowie directly connected the act of healing to the efficacy of Christ’s death on the cross.[30] Through his death, Christ triumphed over Satan and conquered sin and sickness, making salvation and healing equally and universally available to all believers. To affirm his teachings, Dowie published countless testimonies that linked divine healing to the atonement. Testifying to his healing after Dowie prayed for him, one person remarked: “Christ atoned for all sickness and diseases as well as for all sin and sorrow. He took them on the cross.” Through this and other testimonies, Dowie consistently emphasized how Christ secured both salvation and healing through his atoning sacrifice on the cross.

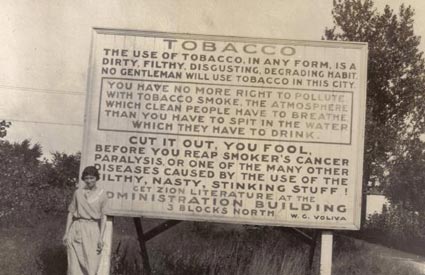

Sign welcoming people to Zion City, Illinois.

Second, all sickness is sourced in the demonic. Rejecting the Reformed model that insisted that sickness was given according to divine providence and was to be endured with passive resignation, Dowie asserted that only Satan is the author of sickness and disease.{[32] “It cannot be for God’s glory that any of His children should be unhealed,” Dowie declared, “since God is never glorified in our sickness anymore than in our sin, for both sin and sickness are clearly Satan’s work.” [33] Considering sin and sickness as collaborative devices used by Satan to keep humanity in bondage, Dowie argued that Christ’s purpose for coming was to destroy the work of Satan and bring complete salvation and healing to sinful and suffering humanity. Leaving no room for the sovereignty of God or the natural laws of nature, Dowie drew battle lines between Satan and Christ; people either side with the devil and remain in their sins and sicknesses, or they come to Christ and receive salvation and healing through his atoning sacrifice.

Third, repentance and faith precedes and sustains healing. Embracing the broader soteriological implications of the atonement, Dowie articulated that individuals must first accept Christ as their Saviour before they accept him as their Healer. “I declare that until a man has quit his sins,” Dowie asserted, “he cannot be healed…I further declare that repentance toward God must be followed by faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, and that salvation is precedent to healing.”[34] Since faith was the means by which healing was apprehended, Dowie maintained that healing could never be received by a sinner; only those who were regenerated and exercised their faith were healed. Furthering his theological argument to an extreme degree, Dowie went on to claim that, “it is the privilege of all who believe in him [Christ] to enjoy perfect and perpetual bodily health.”[35] As implausible as this declaration is, it logically corresponds with Dowie’s soteriological perspective; since the atonement provides enduring salvation, it must also provide enduring health. On the other hand, when believers became sick, it is undeniable evidence that they have unconfessed sin or insufficient faith.[36]

Zion City, Illinois.

Fourth, avoiding demonic influences such as medical treatment and pork products were critical to preventing further afflictions and maintaining physical health. Often railing against doctors and drugs, Dowie taught that seeking the help of a physician demonstrates a complete lack of faith in Christ. “You may take the Bible and search it from Genesis to Revelation,” Dowie stated, “and you can not bring me a passage where it is written: ‘If any of you is sick, let him call for a doctor.’”[37] For Dowie, divine healing was only effectual when sick people transfer their faith from human efforts to the victorious Christ. In addition to his distain for medical treatment, Dowie also demanded that all pork products must be avoided. Derived from the Gospel story where Jesus permitted the legion of demons to enter a herd of swine, Dowie contended that “devils have taken possession of pigs ever since.”[38] Since diseases were sourced in the demonic, eating pork subjected people to demonic influences and made them susceptible to physical afflictions.[39] Supporting his anti-pork convictions, Dowie reported, “there is not a case on record of an orthodox Jew having cancer, not one.”[40] Fearing that such destructive influences would undo what Christ had accomplished, ordering the avoidance of doctors, drugs, and pork products was Dowie’s way of preserving the benefits of Calvary for his followers.

Emerging from Dowie’s extreme healing theology is the awkward issue of unanswered prayer. What happens when repentant believers exercise their faith but do not receive their healing? Dowie’s response was unequivocal: “we say that each received according to his faith”[41] Essentially, Dowie argued that since healing has been provided through Christ’s atoning death, it is the individual’s proper exercise of faith that determines whether or not they receive their healing. “While many are healed instantaneously,” Dowie taught, “others, through lack of faith as lack of willingness to comply with God’s requirements concerning consecrated living, go away unhealed, leaving their bodies in the power of the destroyer.”[42] Placing the responsibility for healing solely on sick person, Dowie’s doctrine likely caused many people to feel anxiety and guilt over their inability to produce sufficient faith to be healed. An example of the harmful nature of Dowie’s doctrines surfaced when popular Methodist evangelist R. Kelso Carter contracted malarial fever.[43] Refusing medical treatment and acting only in faith, Carter went to Dowie in search of healing. After praying for the evangelist, Dowie expressed confidence that Kelso would be healed. However, Kelso’s physical condition remained unchanged and he subsequently fell into a deep depression. After six months, Kelso acquiesced and took medicine, fully recovering within a couple weeks. Reassessing Dowie’s views on divine healing, Kelso insisted that Dowie overemphasized the certainty of healing in the atonement. Admitting that God does heal, but not everyone or every time, Kelso and other evangelical leaders began to view divine healing more as a divine favour and only an ancillary rather than essential part of the gospel.

Conclusion

Apart from his grandiose claims and scandalous downfall, Dowie’s healing ministry left an indelible imprint on the American religious landscape of the late nineteenth century. Discovering the healing power of Christ while praying for a dying woman in his native Australia, Dowie linked the source of divine healing to the atonement of Christ. Convinced that Satan is the author of all sickness and disease, Dowie claimed that Christ’s death on the cross defeated the works of Satan and provided both salvation for sinners and healing for the sick. Through the confession of sin and the proper exercise of faith, healing is assured for all believers. Through the avoidance of demonic influences such as medical treatment and pork products, health is maintained. Although many reported being healed through his ministry, Dowie’s optimistic theology overemphasized the certainty of healing. Applying select Scriptures to support his doctrine, Dowie deduced that since healing was proffered to humanity through the atonement, receiving healing was completely dependent upon the faith of the supplicant. Those believers who were unable to manufacture sufficient faith and failed to receive their healing were regarded as spiritual failures. While appearing to accentuate the grace of God through the atoning sacrifice of Christ, Dowie’s extreme theology depicted God as a discriminatory benefactor who only distributes the benefits of the atonement according to the meritorious efforts of the suffering. Despite his unbalanced and harmful theology, Dowie’s unbreakable confidence in the healing power of Christ impacted countless lives and contributed to the emerging Pentecostal movement that continued to proclaim the message of divine healing through the atoning work of Christ.[44]

Bibliography: Burgess, Stanley M., ed., Van Der Maas, Eduard M., ass. ed. The New International Dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003. Cook, Philip Lee. “Zion City, Illinois: Twentieth Century Utopia.” PhD diss., University of Colorado, 1965. Curtis, Heather D. Faith in the Great Physician: Suffering and Divine Healing in American Culture, 1860-1900. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2007. Dowie, John Alexander, ed. Leaves of Healing. Vols. I-XVIII. Chicago: John Alexander Dowie, 1894-1902, Zion City: Zion Publishing House, 1903-1906. Faupel, D. William, “Theological Influences on the Teachings and Practices of John Alexander Dowie,” Pneuma 29:2 (2007): 226-253. Goff Jr., James R. and Grant Wacker, eds. Portraits of a Generation: Early Pentecostal Leaders. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002. Kydd, Ronald A. N. Healing Through the Centuries: Models for Understanding. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1998. Lindsay, Gordon. John Alexander Dowie: The Life Story of Trials, Tragedies and Triumphs. Dallas: Christ for the Nations, Reprint 1980. Synan, Vinson. The Century of the Holy Spirit: 100 Years of Pentecostal and Charismatic Renewal. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2001. Synan, Vinson. The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1997. Wacker, Grant. Heaven Below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Edward Irving: 19th Century Pioneer of the Pentecostal Movement by William Sloos

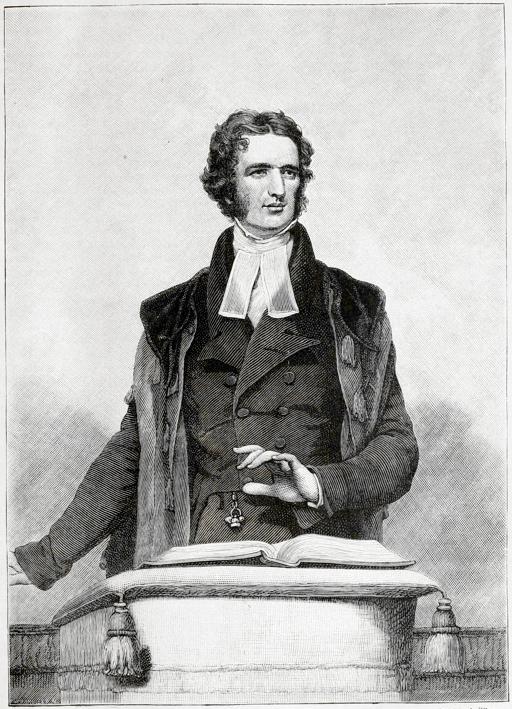

Edward Irving, Presbyterian Minister, Forerunner of the Pentecostal Movement

Introduction

Outside the main entrance of the Old Parish Church in the historic town of Annan, Scotland stands the imposing and distinguished statue of the Rev. Edward Irving (1792-1834).[1]{C} Since his death and for the better part of the twentieth century, he was regarded as little more than an eccentric religious fanatic who was deposed from the ministry of the Church of Scotland for his heretical teachings. However, Edward Irving was not just a religious troublemaker as some would suggest, but should be considered a courageous and uncompromising Pentecostal pioneer who believed and preached on the baptism of the Holy Spirit and allowed the gifts of the Holy Spirit to operate within his church. In spite of the respected traditions of the Presbyterian faith and the determined threat of expulsion from the Presbytery, Irving would not compromise his Pentecostal convictions in light of the teachings of Scripture.

Edward Irving was a man who pursued an authentic faith in God, possessed extraordinary skills in the pulpit, and was committed to the apostolic restoration of the church. From an early age, he demonstrated a desire for a personal relationship with God, unobstructed by the forms and traditions of the religious establishment. Through his brilliant intelligence, boundless energy, and extraordinary oratory skills, he took a modest Presbyterian chapel in a forgotten corner of London, England, and transformed it into the city’s largest congregation, attracting thousands of people to his Sunday services. Described as the “greatest orator of the age,” his thunderous and impassioned sermons exhorted people to repent from their sins and ready themselves for the coming judgment.[2]

Convinced that Christ was about to send a Pentecostal outpouring and restore the apostolic gifts to the church prior to his imminent return, Irving boldly encouraged people to seek the baptism of the Holy Spirit. Accused by the Presbytery of allowing the gifts to function in his service, he stood on the evidence of the Scriptures and refused to recant. When barred from his church, he started a new church based upon the five-fold apostolic ministry of the early church. Tragically, Irving never personally received any charismatic gifts and was relegated to a subordinate position within this church; a victim of his own theology, he was eventually forgotten. Despite Irving’s demise, he was a courageous and uncompromising pioneer of the Pentecostal movement, which seventy years later, was to spread around the world and become the third force of Christendom.

Irving’s Early Years

Edward was born as the second of three sons to Gavin and Mary Irving on August 4, 1792, in Annan, a town in south-west Scotland.[3]{C} Edward’s father worked as a leather merchant and was able to provide a reasonably comfortable life for his wife and family, which also included five daughters.[4]{C} Edward was stronger and taller than most boys his age and he was often outdoors, exploring the countryside and swimming in the ocean. According to Scottish historian Margaret Oliphant, author of a biography of Irving written in 1862, though he was vivacious and adventuresome, he was also more mature and intellectual than his peers and was often more concerned with adult matters than the amusements of childhood.{C}[5]{C} Edward was also an independent thinker and became interested and involved in religious and social activities uncommon to most school-aged children.[6]

Like most of the citizenry of Annan, Edward and his family regularly attended the local Presbyterian Church, otherwise known as The National Church of Scotland. However, when Edward was ten or eleven years old, he occasionally attended the Church of the Seceders,{C}[7] a separatist congregation that assembled in an upstairs meetinghouse in Ecclefechan, a village about six miles away. The Church of the Seceders was a group of pious believers who parted ways with the National Church because of its increasing doctrinal and moral laxity and religious tedium. Over the previous twenty years, a number of “seceding” churches were established throughout Scotland, preserving a spiritual vitality and evangelical fervour among many people. The pastor of the church Edward attended was the Rev. John Johnstone, a man of strong convictions who was committed to reaching “lost souls” for Christ.[8] The Church of the Seceders and the ministry of pastor Johnstone were to have a considerable influence on Edward and, by the time he was twelve years old, he acknowledged having a desire to become a minister.[9]

Edward’s parents instilled a high value of education in their son and when he was thirteen he left home to attend university in Edinburgh.[10]{C} While in university, Edward distinguished himself as an outstanding student, especially proficient in mathematics, geography, Latin and chemistry.[11]{C} He took great pleasure in reading and immersed himself in the adventures of his favourite books, such as John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Don Quixote, and Tales from the Arabian Nights.{C}[12]{C} When Edward thought about his future as a minister, Arnold Dallimore notes that he did not want to be dull and boring like most ministers, but “he would be different- he would be powerful…like those of his favourite authors”.[13]{C} Edward became active in the debating society and began cultivating his public speaking abilities, displaying a natural fluency of speech and a rather tenacious self-confidence.{C}[14]{C} At the age of seventeen, Edward received his Master of Arts degree and shortly thereafter, commenced his divinity training part-time while teaching at a parish school in the town of Haddington, twenty miles south-east of Edinburgh, Scotland. His enthusiasm and unusual teaching methods quickly earned him a reputation as a very skilful educator among his colleagues and students.[15]

After two years in Haddington, Edward was invited to become the head schoolmaster at a new school in the town of Kirkcaldy, Scotland.[16]{C} There he befriended the Rev. John Martin, the local Presbyterian minister and was introduced to his daughter, Isabella. Edward was fond of Isabella and after courting for several years they would eventually marry have a family together.[17]{C} His interest in theology persisted and upon completion of his divinity courses, he received a probationary ministerial license from the Presbytery of Kirkcaldy. Through his relationship with Rev. Martin, Irving was granted several preaching opportunities at the local parish, however many in the congregation disliked his sermons, considering them to be unusual, overly verbose, and difficult to follow.[18]{C} According to Oliphant, some parishioners even described his preaching style as “thunder-strained” and “strangely different from the discourses of other orthodox young probationers”.{C}[19]{C} Irving’s unusual preaching style was indeed different from the average preacher, and though considered too urbane for the humble flock in Kirkcaldy, his distinctive oratory talents would soon distinguish him as the most powerful preacher in the National Church of Scotland.

The Call to Ministry

Irving longed for the day when he would be able to employ his preaching skills and pastoral abilities on a permanent basis. During this time, the National Church of Scotland operated under a “patronage system”[20] in which a minister could obtain a pastoral charge through the influence of certain important individuals.[21]{C} Irving, as evidence of either his personal integrity or his stubborn pride, flatly refused to subject himself to such contemptible ecclesiastical politics and instead desired to be summoned to the pulpit solely based on his own merits and abilities. However, after waiting several frustrating years without any invitations, he decided to resign his position as head schoolmaster and return to Edinburgh to explore his ministry opportunities.

In 1819, when Irving was twenty-six years old, he received a special invitation from the distinguished Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers to become his assistant at the renowned St. John’s Church in Glasgow, Scotland.[22]{C} He enthusiastically accepted the offer and quickly immersed himself in the life of the parish and the responsibilities of pastoral ministry. Though some parishioners felt he lacked conviction and tended to parade his knowledge in the pulpit, he excelled in pastoral visits, showing genuine concern for those less fortunate, visiting their homes, holding their sick babies, and even giving away most of his income to those suffering or in material need.{C}[23]{C} However, the relationship between Irving and Chalmers, though always cordial, was never completely pleasing to either of them. Chalmers was always concerned that Irving might do or say something extreme or embarrassing and Irving chaffed at the subordinate position.[24]{C} Irving’s ambitions were greater than being an assistant pastor and he continued searching for opportunities to escape Chalmers’ restrictive grip. As he waited, he completed his ministerial probation and in 1822, was ordained by the Annan Presbytery of The National Church of Scotland.[25]{C} Soon after his ordination, Irving received invitations from two Presbyterian churches- one in Jamaica and one in New York City, requesting him to become their pastor. As he was considering the offers, a third offer surfaced from a modest church in London, England that he would promptly accept, providing him the opportunity to his freely express himself and his radical convictions.[26]

Edward Goes to London

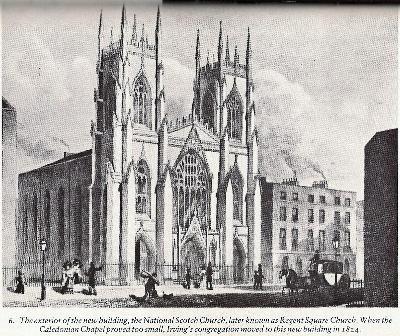

The Caledonian Chapel was a small and struggling outpost of the Kirk,[27] situated in a neglected and impoverished area of London, England. The church had been without a pastor for over a year, the congregation was dwindling to around fifty people, and there were murmurings of closing the doors permanently.[28]{C} On the second Sunday in July, 1822, the twenty-nine year old Rev. Edward Irving ascended the pulpit and preached his first sermon as the new minister of the Caledonian Chapel.{C}[29]{C} To the parishioners, his arrival merely represented a remote chance of reviving the neglected church, but to Irving it was the opportunity of a lifetime. He wrote to a friend concerning his new charge saying, “You can not conceive how happy I am here in the possession of my own thoughts, in the liberty of my own conduct, and in the favour of the Lord.”[30]{C} Edward believed he had finally stepped into the role he was destined for, and with tremendous energy and enthusiasm he began delivering powerful and persuasive sermons that were brimming with emotion and authority. Word spread about this forceful and dynamic young Scotch minister and soon those who had forgotten about the old chapel returned to their pew benches, bringing their friends and neighbours with them to see the latest attraction for themselves.

Within six months, the Caledonian Chapel, which seated about five hundred people, was filling to over a thousand.[31]{C} Sunday after Sunday, people crammed into the church, filled every seat, stood in the aisles, overflowed into the vestibule, and spilled out into the streets all hoping to experience the unparalleled preaching of the Rev. Irving. His ever-increasing popularity soon attracted London’s notables: lawyers, physicians, actors, artists, diplomats, “fine ladies”, and renowned people such as the English poet William Wordsworth and the Honourable George Canning, Britain’s foremost statesman and later prime minister.[32]{C} People from all spheres of life were attracted to Irving’s rich and rolling orations, his consuming desire for the Lord, and his zealous condemnation of sin, likened to that of an Old Testament prophet.{C}[33]{C} Renowned English essayist Charles Lamb lauded Irving as the “Boanerges of the Temple,” [34] referring to his thunderous and untamed nature from behind the pulpit.[35]{C} True to his word, Irving was not dull and boring like all the other ministers, he was different- and he was taking London by storm.

As Irving’s popularity swelled throughout the metropolis, the elders of the Caledonian Chapel dusted off their plans for a new National Scotch Church better suited to accommodate the throngs of people and appeal to London’s upper class. As the new gothic edifice was being erected, Irving also went to work, publishing a series of sermons in four volumes: For the Oracles of God, Four Orations, For Judgment to Come, and Argument in Nine Parts.[36]{C} Matching his potent and mesmerising preaching style, his books centered upon the fulfillment of biblical prophecy and the imminent return of Christ. They were purposely confrontational in style and language, railing against the religious stagnancy of the times and criticizing the spiritual blindness of the current generation of ministers.[37]{C} With characteristic outspokenness, Irving also attacked the corruption in the government, bewailed the materialism spawned by the new industrial age, and denounced the evils of contemporary society. He unashamedly declared that the church was living in the “last days”, the coming of the Lord was very near, and people everywhere need to repent from their sin and turn to God. Though the judgmental nature of his books offended some people, he continued to attract the crowds and, by the time the church moved into their new landmark cathedral at Regent Square in 1827, they were the largest congregation in the capital.{C}[38]

The eschatological nature of Irving’s sermons and books struck a nerve with the current spiritual consciousness of the English population. People frequently viewed the recent political events in light of Biblical prophecy and many were convinced they were living in the “end times”. The American War of Independence in 1776 was considered the work of the spirit of lawlessness and the undermining of the God-given order of government.{C}[39]{C} The French Revolution of 1789 hit closer to home and kept many people in a long-standing state of anxiety and fear.[40]{C} The subsequent rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and his march across Europe caused many in England to consider him “devil-inspired” and were convinced he or his son would eventually prove to be the Antichrist.[41]{C} Among the religious community, Oliphant states that the people earnestly believed that “the Lord was coming visibly to confound his enemies and vindicate his people!”[42]{C} These eschatological sentiments created a hunger for practical theology as opposed to the abstract thought found in the established traditions of Protestantism.[43]{C} People were no longer interested in deep searches for theological truth that was being dispensed by the state church; they were searching for straightforward answers to their current state of affairs. It was under such finely tuned conditions that Irving would undertake a radically new understanding of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit.

The Albury Conferences

In this heightened spiritual atmosphere, Irving began participating in the Albury Conferences, an annual six day prophetic symposium where like-minded ministers and laymen gathered to discuss biblical prophecy and its literal and imminent fulfillment.{C}[44]{C} Hosted by banker Henry Drummond, this select company of forty-nine men from a variety of social and religious backgrounds formed the so-called “school of the prophets”.[45]{C} According to James E. Worsfold, during these meetings Irving noted that there was a strong sense of the presence of the Holy Spirit in their midst and likened their gatherings to the wise virgins of Matthew 25, who waited earnestly for the coming of the bridegroom.{C}[46]{C} He also shared how, in one of the private quarters of the Albury house, he was “in the Spirit”, testifying that he met his Lord and Master “whom he would soon meet in the flesh”.{C}[47]{C} The conferences would have a tremendous influence on Irving’s faith and doctrine, stirring within him the desire to seek the Lord for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit as on the day of Pentecost.

One of the members of the conference, a man by the name of Hatley Frere, propounded a new eschatological scheme of prophetic interpretation according to a futuristic method conceived by Spanish Jesuit, Ribera.[48]{C} He contended that most of the biblical prophecies had been fulfilled, the world was about to enter the period of greatest suffering, and the return of Christ was literally only a few years away.[49]{C} While Frere aroused a picturesque outlook of the impending apocalyptic judgment, Irving, knowing that the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was to occur before the return of Christ, began believing that the church was on the brink of a Pentecostal restoration. He believed that the Holy Spirit was about to baptize his people again, empowering them with the gifts of the Holy Spirit and the authority of the apostles and prophets.[50]{C} So convinced of this imminent Pentecostal restoration, he felt that it could be at any moment when his church would start to experience the “latter rain” as prophesied by Joel in the Old Testament.[51]

The influences of the Albury Conferences launched a theological revolution in Irving’s personal life and pastoral ministry at the Regent Square church. On the verge of a new world of realized eschatology and pneumatology, Irving began preaching that the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was near and would herald the return of Christ. He began emphasizing the need for prayer and formed a group of like-minded parishioners who would meet together every Sunday morning prior to the public service to seek the Lord for this new Pentecostal outpouring.[52]{C} Prayer, according to Irving, was the biblical model for accessing and receiving the supernatural power and apostolic gifts of the Holy Spirit. According to P. E. Shaw, when describing the prayers of their early morning meetings, Irving stated, “We cried unto the Lord for apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and teachers, anointed of the Holy Ghost, the gift of Jesus, because we saw it written in God’s Word that these are the appointed ordinances for the edifying of the body of Jesus”.[53]{C} For Irving, these meetings would become the primary vehicle for the practical implementation of his eschatological and pneumatological doctrines that would profoundly affect the course of his ministry at Regent Square.

The Nature of Christ

Shortly after inaugurating these prayer meetings, Irving started coming under fire for his unorthodox doctrine of the human nature of Christ. In attempting to draw a link between the power Jesus possessed and the power available to all believers, Irving began teaching that Christ, in coming to earth, did not take the human nature possessed by Adam before the Fall, but after the Fall, and therefore had a corrupted human nature.[54]{C} Since his human nature was corrupt, he was subject to the same evil tendencies and temptations as all humans and his life on earth was a constant battle against sin. His ability to conquer sin and perform miracles derived from his baptism in the Holy Spirit, bestowed upon him by his father at his water baptism.[55]{C} From that point on, the power of the Holy Spirit was so strong in his life that, even though his nature was sinful, his life remained sinless.[56]{C} He thus reconciled fallen humanity back to God by living a sinless life, having defeated the power of sin through the power of the Holy Spirit.[57]

Consequently, Irving believed that the same Holy Spirit that empowered Christ to overcome sin and perform miracles was also available to every believer through the baptism of the Holy Spirit. Thus, when a believer receives the baptism in the Holy Spirit, they possess the same power Christ possessed and, though they still have a fallen nature, they can have victory over sin and perform miracles.[58]{C} Irving’s Christology united with his pneumatology became a theological launching point for his preaching on the baptism of the Holy Spirit.[59]{C} According to Colin Gunton however, this controversial doctrine did not originate with Irving, but was mostly likely a modification of the theology of John Owen, a seventeenth century non-conformist theologian.{C}[60]{C} Nevertheless, the majority of parishioners at Regent Square welcomed his teachings, even stirring some to begin seeking the baptism of the Holy Spirit.[61]{C} However, Irving’s unorthodox views started raising some eyebrows with the theologically learned and would eventually capture the attention of the National Church.

On Sunday, October 28, 1827, the reverend Henry Cole, an Anglican vicar, theologian, and translator of Martin Luther’s The Bondage of Will (1823), arrived late for the service at the new cathedral at Regent Square.[62]{C} Cole had heard the rumours about Irving’s peculiar views on the incarnation of Christ, but wished to attend the service to hear the matter for himself. The little that Cole heard shocked him deeply and confirmed the reports that Irving, London’s most celebrated preacher, was proclaiming that the substance of Christ’s human nature was essentially sinful. According to Cole, Irving had declared that Christ’s greatest accomplishment was his ability to overcome sin through the power of the Holy Spirit and thereby rendering the cross of little significance.[63]{C} Cole confronted Irving after the service and, unsatisfied with the minister’s response, began publicly accusing him of teaching heresy.{C}[64]{C} Irving chose not to respond to the accusations, hoping the controversy would die down, but to his surprise, suspicions over his “sinful substance” doctrine began to increase.

Preaching Tours of Scotland

In the spring of 1828, Irving, now thirty-six years old, left for a preaching tour of his native Scotland, burdened in his heart to warn his fellow Scots of the soon return of the Lord and the approaching judgment.{C}[65]{C} While in the Gare Loch, a district along the west coast of Scotland, Irving met McLeod Campbell, a fellow minister of the Kirk who would become one of Irving’s closest friends. Campbell was convinced that the “charismata”- the miraculous gifts possessed by the apostles, did not cease with their demise, but were abandoned by the church because of a lack of faith and coldness of heart.{C}[66]{C} During Irving’s visit to Campbell’s church, a ministerial probationer by the name of A.J. Scott, preached a sermon on the charismatic gifts of 1 Corinthians 12. In his message, he declared that the baptism of the Holy Spirit was an experience distinct from and subsequent to the baptism of repentance.[67]{C} According to Worsfold, at the conclusion of the sermon, a number of people in the congregation began speaking in tongues and prophesying.{C}[68]{C} Irving’s witness of these charismatic manifestations at Campbell’s church impressed him greatly and personally confirmed what he had been expounding from Scripture for some time. Describing his meeting with Scott, Irving would later write, “As we went out and in together he used often to signify to me his conviction that the spiritual gifts ought still to be exercised in the church; that we are at liberty and indeed bound to pray for them”.[69]{C} Shortly thereafter, Irving invited Scott to become his assistant in London; Scott accepted the position, but only on the condition that he would not be under any doctrinal requirements of any kind.[70]

Irving resumed his preaching tour through Scotland, proclaiming his eschatological and charismatic message to overcrowded churches and fellowship halls. While in Kirkcaldy, where he served as head schoolmaster in his early twenties, his coming was so highly anticipated and the religious fervour so intense, that the local Presbyterian Church began to fill to a level beyond its load bearing capacity. Before the start of the service, the galleries, crammed with enthusiastic worshippers, started to crack and tremble, then under the excess weight of the crowd they suddenly collapsed and crashed to the floor beneath, killing several people and injuring many others.[71]{C} As Irving hurried to assist those in need, a voice in the crowd blamed him for the terrible calamity that was unfolding around them. Irving, saddened by the tragedy and wounded by the accusation, believed that the wrath of God was already being poured out.[72]{C} He would return to England, only to discover that the opinions of him had worsened in his absence and he was about to face another accusation, that of heresy by the London Presbytery.

Accused of Heresy

Hostility to Irving’s doctrine of “Christ’s sinful flesh” continued to grow throughout England and Scotland and an increasing number of ministers who opposed his teaching began to voice their opposition officially through the courts of the Church.[73]{C} Irving’s friends, McLeod Campbell, A.J. Scott, and Hugh Maclean, a previous probationer under Irving, were already under increasing pressure by the Church of Scotland because of their allegiance to Irving’s controversial doctrine. In an attempt to clarify his doctrinal position on the nature of Christ and protect him and his friends from further interrogation, Irving wrote his third book, The Opinions Circulating Concerning our Lord’s Human Nature, Tried by the Westminster Confession of Faith.[74]{C} In his argument, he attempted to explain how his detractors were taking his teachings out of context and how the Westminster Confession of Faith[75] does not contradict his doctrine but could theologically accommodate his point of view. Nevertheless, on November 30, 1830, the London Presbytery found Irving guilty of heresy and, according to Gordon Strachan, concluded their report saying that his doctrine contained “errors subversive to the great doctrines of Christianity, and that it was dangerous to the welfare of the Church of Christ.”[76]{C} Irving however, was free on a technicality; his credentials belonged under the authority of The Church of Scotland and the London Presbytery had no legal jurisdiction to depose him from the pulpit. Unbowed, he separated himself from the London Presbytery and continued to minister as an independent with the wholehearted support of the trustees of his church. The Church of Scotland however was not amused and approved a motion to the effect that if Irving should appear in Scotland, they would take necessary action against him because of his heretical teachings.{C}[77]

Outbreaks of Glossolalia in Scotland

During the winter of 1830, while Irving was preoccupied with the defence of his Christology, events were unfolding on the west coast of Scotland that were to have a profound impact, not only on Irving’s position at Regent Square, but also on the entire Church of Scotland. The wind of Pentecost was blowing and supernatural manifestations of the Holy Spirit began occurring among a number of people. Worsfold states how a local medical doctor named Dr. Norton recorded how several people who were on their deathbeds experienced outbursts of the Holy Spirit, “both in way of utterance and apparent glory”.{C}[78]{C} He also noted that at a number of house meetings, people reported having supernatural visitations and miraculous physical healings.[79]{C} At a prayer meeting in Port Glasgow, he described how the Macdonald brothers received the baptism of the Holy Spirit and spoke in tongues, even noting that they “continued to do so for the rest of their spiritual life”.{C}[80]{C} According to an eyewitness account, the doctor also relayed that the prophetic message at these meetings was, “Send us apostles, send us apostles.”[81]

In the town of Fernicarry in the Gare Loch area of Scotland, where McLeod Campbell and A.J. Scott had been teaching on the Pentecostal baptism and the restoration of the charismatic gifts, a young woman by the name of Isabella Campbell (no relation to McLeod Campbell) captured the attention of the entire community. Sick with tuberculosis and bedridden, she claimed that as she meditated on the things of God, she would have out-of-body experiences and spontaneous ecstatic moments in the Holy Spirit.[82]{C} After she died, people from all over the area would make pilgrimages to the Campbell home to pay homage to Isabella. In this spiritually heightened atmosphere, these people started waiting on Isabella’s sister Mary for additional spiritual experiences. Mary Campbell, who was grieving the death of her fiancé and also suffering from poor health, suddenly became the poster child for the Pentecostal outpouring in Scotland. As she lay sick in her bed, an increasing number of people began surrounding her, anticipating some type of manifestation of the Holy Spirit.[83]{C} A.J. Scott, now Irving’s assistant at Regent Square, would often travel to Fernicarry to visit with Mary, teaching her the distinction between salvation and the experience of the baptism of the Holy Spirit and advising her to study the book of Acts. Scott had frequently taught this “two-stage” concept of the Christian life in McLeod Campbell’s church in Gare Loch and was convinced that this was the proper interpretation of Scripture.[84]{C} Shortly thereafter, Mary wrote a letter to her pastor, Rev. Robert Story, who would later write an account of her life, telling him that she was experiencing a new level of intensity in her relationship with the Holy Spirit and that she is looking forward to receiving two of the apostolic gifts: the gift of tongues and the gift of prophecy.[85]

On Sunday evening March 28, 1930, Mary Campbell was miraculously healed and, as she rose from her deathbed, she suddenly broke out in an unknown language.[86]{C} Witnessed by several friends, she filled the room with incomprehensible sounds, convinced it to be the baptism of the Holy Spirit like on the day of Pentecost. Believing that tongues were actually known languages, she claimed that she was speaking the dialect of a people on a remote island in the South Seas- the Pelew Islands, a people of whom she had been reading;[87] she also claimed that she received the additional gift of “automatic writing”.[88]{C} According to Oliphant, this homely young woman entered into the full-time career of a “prophetess and gifted person” and started giving demonstrations of her supernatural power before crowed assemblies.{C}[89]{C} Word of Mary’s Pentecostal baptism spread rapidly, stirring the entire religious world of Scotland and England. For the people of Gare Loch, Mary’s experience became undeniable evidence of the presence and power of God, confirming their faith and their belief that the sought after outpouring of Holy Spirit had finally arrived.[90]